Below is a subjective list of 15 very compelling reads featuring an unreliable narrator. They are bound to leave you grappling for the truth!

I neither expect nor solicit belief

–Edgar Allan Poe, The Black Cat

Trying to define an unreliable narrator leaves us tangled in the unenviable position of trying to explain a reliable narrator in the first place. Any first-person narration is bound to be unreliable. The mind always attempts to distinguish truth from falsehood. It insists upon familiarity; it hungers for clarity. So, ‘unreliable’ is an odd, amorphous term. In the field of literary studies, the concept of the unreliable first-person narrator was first identified by Wayne C. Booth. Later elaborations and theorizations came from Roland Barthes and Percy Lubbock, among others. As a literary device, however, the unreliable narrator has been used by everyone, from Laurence Sterne and Edgar Allan Poe to Gillian Flynn, and is a familiar concept to readers. Part of the fun of reading works with storytellers who cannot be trusted is trying to figure out if the great and the powerful are really what they claim to be or if it’s all a cheap trick pulled off by a tinkerer with smoke mirrors and sleight of words. It figuratively keeps readers on their toes, always approaching the narrator with caution.

Without further ado, here is a list of 15 novels that use the unreliable narrator with ingenuity to great success. The characters contained within this list span an entire spectrum – Some are addicts, some delusional, some merely misguided; some are intentionally misrepresenting and distorting truths, while others are interpreting things in a way that may be judged as wrong. Sometimes, the truth is revealed in the denouement. In other cases, the books tread a fine line between knowledge and madness and utterly resist interpretation. All are compelling. Naturally, SPOILERS abound.

PS: This list is completely objective. The selection of entries has not been colored by personal preferences and prejudices. These are, objectively, the fifteen best books with an unreliable narrator. Why would I lie to you? I am only an impartial observer of things as they happen. Trust me about it.

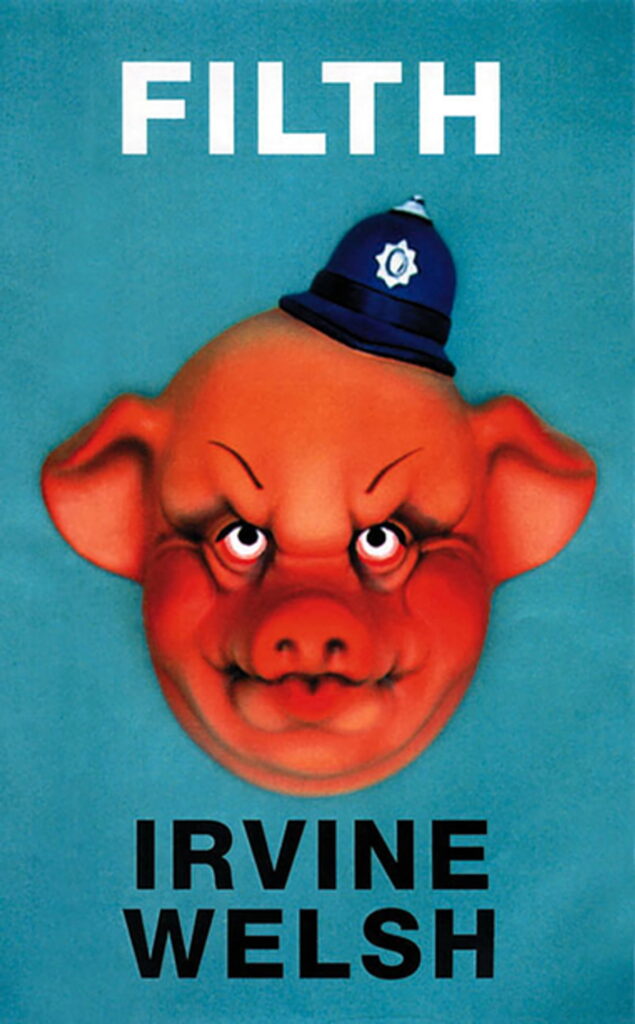

- 1. Filth–Irvine Welsh (1998)

- 2. We Have Always Lived in the Castle–Shirley Jackson (1962)

- 3. The Good Soldier: A Tale of Passion–Ford Madox Ford (1915)

- 4. The Remains of the Day–Kazuo Ishiguro (1989)

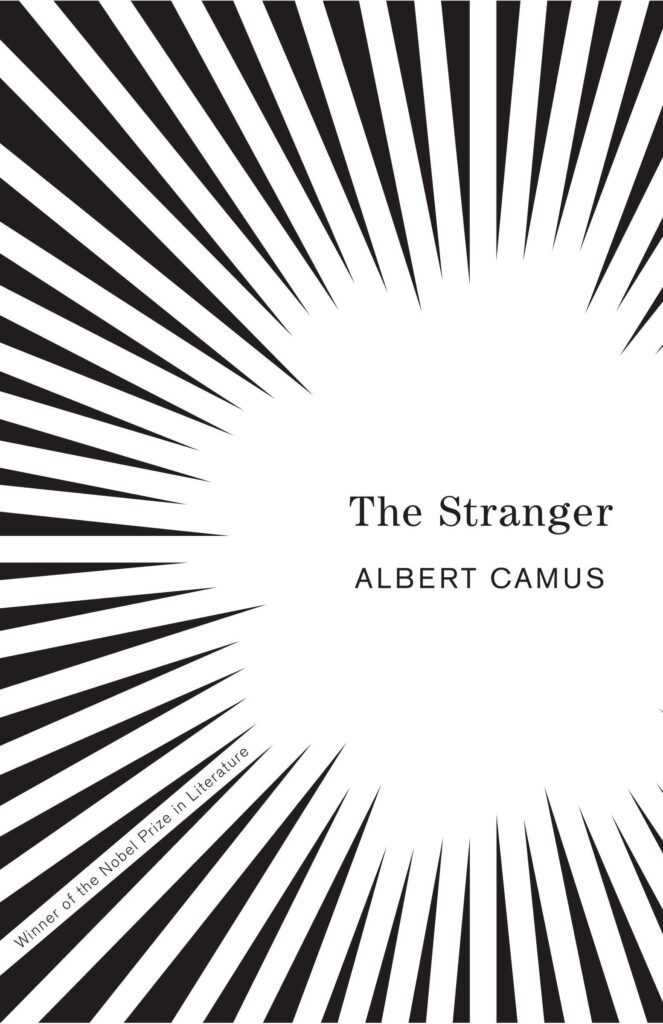

- 5. The Stranger–Albert Camus (1942)

- 6. Emma–Jane Austen (1815)

- 7. House of Leaves–Mark Z. Danielewski (2000)

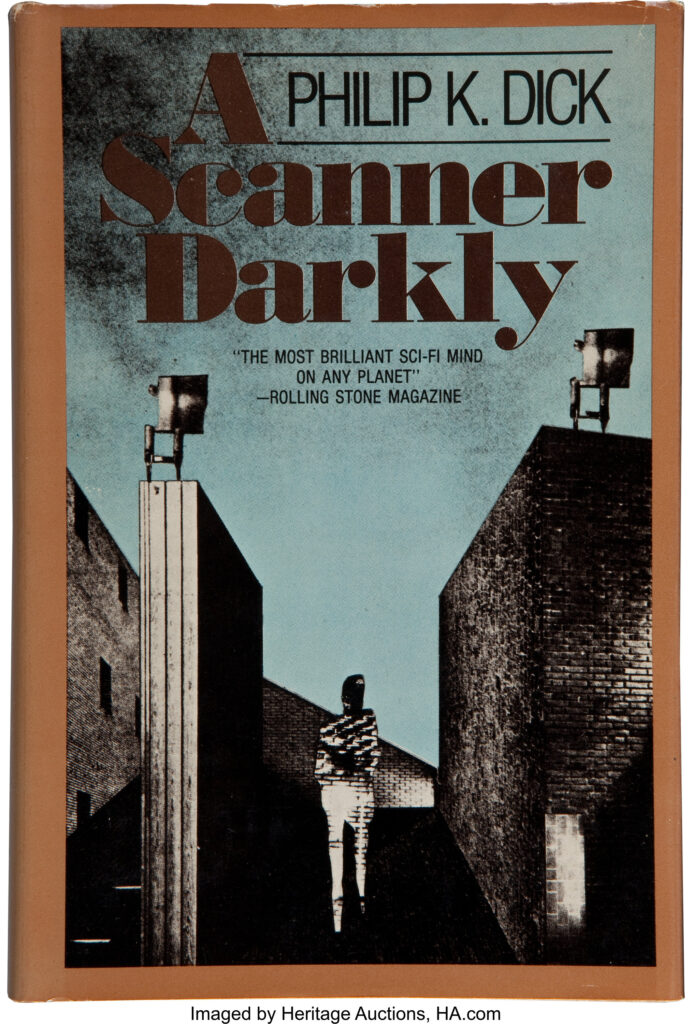

- 8. A Scanner Darkly–Philip K. Dick (1977)

- 9. Code Name Verity–Elizabeth Wein (2012)

- 10. The Turn of the Screw–Henry James (1898)

- 11. Invisible Monsters–Chuck Palahniuk (1999)

- 12. Pale Fire–Vladimir Nabokov (1962)

- 13. We Need to Talk About Kevin–Lionel Shriver (2003)

- 14. Drood–Dan Simmons (2009)

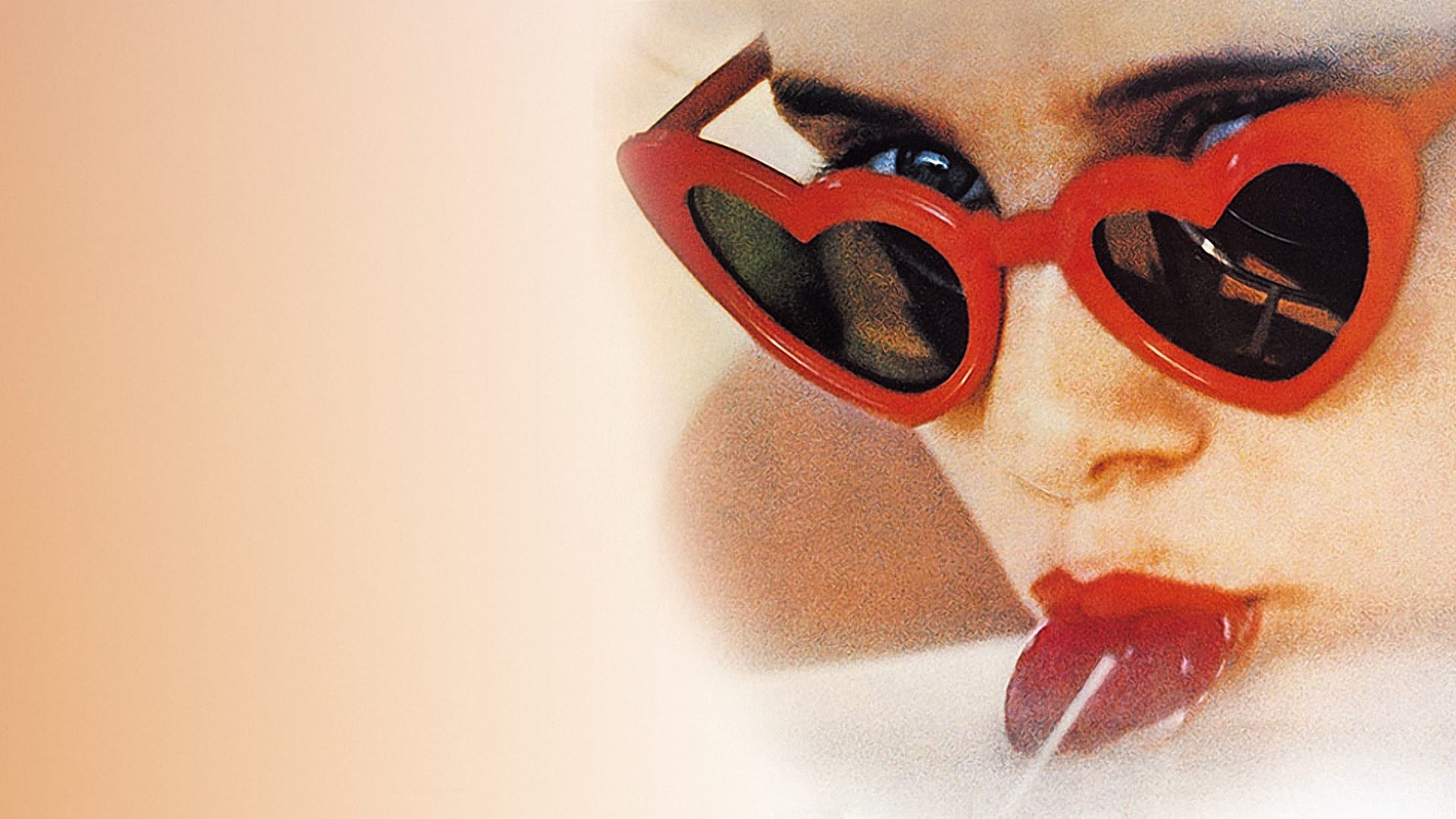

- 15. Lolita–Vladimir Nabokov (1955)

1. Filth–Irvine Welsh (1998)

Irvine Welsh’s 1998 novel is an endurance test. The book is an onslaught of dirt, disease and violence; it’s only for those with the strongest constitution. Detective Sergeant Bruce Robertson is, to put it mildly, an awful man. He’s a sadist, racist homophobe with a drug and alcohol habit, and he is up for a promotion. He plays mind games with his colleagues and lovers that cross the line into unquestionable abuse. Nothing gives him as much pleasure as ruining other people’s lives. He’s a homewrecker with his own broken marriage. He’s also the lead investigator in the homicide of a black journalist.

Welsh takes inherently repulsive concepts and creates an obscenely humorous trainwreck of a story. We follow Robertson as he sinks deeper into paranoia and delusion, with moments of startling self-awareness thrown in. And yet he continues. It makes for a vividly loud, boisterous, and terrifying result. Enduring Robertson leaves one feeling stained and worried about contagion. Without a doubt, Filth is one of the filthiest books I’ve ever experienced. Welsh reaches for total sadism and ramps up the sheer insanity as we near the bitter end.

2. We Have Always Lived in the Castle–Shirley Jackson (1962)

Shirley Jackson’s 1962 novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle is another classic work that uses an unreliable narrator. Widely accepted as Jackson’s masterpiece, the book is narrated by Mary Katherine “Merricat” Blackwood, an eighteen-year-old girl living on an estate with her agoraphobic sister and their ailing uncle. To reveal any more would be to spoil the perfect rug-pull that Jackson executes. Jackson’s skill lies in leading us to believe in this disarmingly disturbed protagonist and to root for her. In doing so, we are completely blinded to the truth and shocked at the final revelations. The book is a masterpiece of camouflage and obfuscations, filled to the brim with strangely sympathetic but nonetheless eerie acts of childish horror and magic.

Also Read: Shirley [2020] Review – Portrait of a Literary Icon through a Compelling Biofiction

3. The Good Soldier: A Tale of Passion–Ford Madox Ford (1915)

Ford Madox Ford’s 1915 novel is set just before World War I. It focuses on two couples, the aristocratic English couple Edward and Leonora Ashburnham and the wealthy American Dowells, who meet at a spa in Germany. The story is told in a dubious first-person narration by John Dowell and revolves around Edward Ashburnham and Florence Dowell’s chronic inability to stay faithful to their partners. Dowell presents himself as a sexless, mild-mannered, long-suffering, self-effacing cuckolded husband.

Even the good soldier of the title refers to Edward, which is our first clue that nothing is really as it seems and that Dowell’s disengaged helplessness may be hiding somewhat sociopathic tendencies. Therein lies the complicated genius of the novel. Ford mires us in a non-chronological and horribly knotty narrative. Dowell himself remains in the shadows. Is he the victim of other people’s manipulations and passions? Or is he cleverly manipulating facts to serve his own ends? Discrepancies in Dowell’s narration widen, and we are left wondering about true outcomes, erroneous reports, and internal contradictions.

4. The Remains of the Day–Kazuo Ishiguro (1989)

Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day is the story of Mr. Stevens, an ageing English Butler looking back and reflecting on the days of his service at Darlington Hall, especially in the years leading up to World War II. Now, Stevens would be deeply offended if he knew he was being called unreliable. He does not lie to the readers or even deliberately mislead them. It really just wouldn’t be proper. The reader quickly comes to realise that his understanding of events as they happened and what really happened are two very different things. Stevens is not a man much given to intellectual rigour. He is intensely loyal to his old master because that is his duty as a butler. His education has been to always look the other way, especially when it comes to his master, who, as it becomes obvious to readers, is far from the infallible gentleman Stevens portrays him as. Stevens is emotionally stunted and has dedicated his entire life to the service of a repulsive man. He’s unfailingly honest, entirely empty and remains one of the perfect examples of an unreliable narrator who is not deliberately misleading but is himself misguided.

5. The Stranger–Albert Camus (1942)

Albert Camus’ The Stranger is a slim but deeply-layered study of estrangement and alienation. Initially, it appears that the first-person narration would allow openness and honesty with the readers. But it increasingly becomes evident that Meursault, the protagonist, is ill-equipped for any attempts at honesty. He inhabits a solipsistic universe with his unique moral scruples or lack thereof. He drifts through life without passion, without attachments. This limited perspective is curtailed further by Meursault’s estrangement from the world.

The book, however, also deals with the idea that our beliefs, perceptions, awareness, and motivations are fundamentally inaccessible to other people, leading to profound misunderstandings and misinterpretations. Others constantly misinterpret Meursault. He is a stranger to his own mind. He spends little time trying to explain his actions, even to himself. He cannot communicate this distance from himself to others. His telling of events and his perspective are warped and one-sided, and his philosophical conclusions hardly make sense to others – the vivid portrayal of psychological interiority points to moral emptiness.

6. Emma–Jane Austen (1815)

A variation on the trope, Jane Austen’s Emma, is narrated solely by the author herself but exclusively from the title character’s point of view. Austen is Emma’s interpreter and our guide through this world. This deliberate choice lets Austen deftly, but in plain sight, give readers every reason to question Emma’s headlong conclusions. Emma is a classic unreliable narrator to other characters within her own world. Emma’s wishful and wilful narratives consistently mislead those who depend entirely on her versions of the story. In fact, Emma is not the only unreliable narrator. She is misled in her turn by various camouflaging accounts and confusions where she thinks she truly does perceive the real situation. The aspect of reliability is stretched again by characters such as Mrs Weston and Mr Knightley, both of whose assessments are influenced by the nature of their relationship with Emma.

Also Read: Pride and Prejudice: What Makes it Still Relevant?

7. House of Leaves–Mark Z. Danielewski (2000)

A classic in the Weird Lit, horror and malicious house genres, Mark Danielewski’s debut novel – if calling it that even remotely explains what this book is – works with a mile-long list of unreliable narrators. The title page, in fact, credits not Danielewski but two characters from the book. It’s presented as a work of epistolary fiction: the main thread is a faux-academic exegesis about a haunted-house documentary that doesn’t exist, complete with citations that don’t exist (although Danielewski does pepper in quite a few that do). All these academic and anecdotal meanderings are collected into a monograph with added commentary by Johnny Truant, the primary narrator and perhaps the best and most obvious example of this literary device. Truant openly admits to changing the text. His reliability slips away as the readers and Johnny slowly make their way through the manuscript, seemingly eating away at his sanity. His already drug-fuelled ramblings turn into an incoherent, desperate mess of fantasies and nightmares. House of Leaves has been called many things: a home-invasion story, a love story. It’s confusing and disconcerting. For every reader, the effect of House of Leaves is deeply personal and unpredictable. It’s a genre of its own.

8. A Scanner Darkly–Philip K. Dick (1977)

A Scanner Darkly has all classic Philip K Dick themes of confused, blurred boundaries between a persona and real identity and the paranoiac disintegration of identity. Bob Arctor (also known as Fred) embodies the epitome of an unreliable narrator. He is an undercover narcotics agent pretending to be a drug addict. Arctor has to hide his identity from both the police and his druggie friends. Other than the usual smorgasbord of major drugs found both in real life and the story, what’s really wreaking havoc in a dystopic future world is Substance D. It’s a highly addictive psychoactive drug which results in irreversible brain damage.

Arctor’s task is to trace dealers to the source of drug supply, and among the dealers is also his on-and-off girlfriend Donna. Arctor knows the risks involved, but no one is immune or resistant. Was there ever really a doubt that soon the undercover agent would become indistinguishable from his drug addict pals? That was his assigned job, and he did it a little too well. A philosophically and psychologically insightful work on perception, identity, and reality, A Scanner Darkly is an atmospheric, uncomfortable read. Arctor’s loss of control and eventual existential crisis leave readers wondering what, if anything, is at all true.

9. Code Name Verity–Elizabeth Wein (2012)

Elizabeth Wein’s young-adult fiction takes place during World War II and tells the story of two young British women and their friendship. One is an intelligence agent, and the other is a pilot. The book is divided into two sections, with each protagonist getting her own narrative. The story begins after the two friends are separated, following a mission going disastrously wrong. Initially, we meet and follow our first protagonist, the intelligence agent, as she’s captured by the German army in occupied French territory. As a POW, she is forced to tell everything she knows of the British war effort, and the first section shifts between her first-person account of her capture and imprisonment, and a third-person recollection of her friendship with the pilot. The diary is a cobbled and confusing record, streaked with her disgust and humour, leaving readers wondering about her reliability. But it’s only when the second section begins and the pilot, Maddie, tells her side of the story that everything falls into place with a wonderful and shocking climactic twist. The book leaves the readers flicking back and forth to compare the different recounting of events.

10. The Turn of the Screw–Henry James (1898)

The Turn of the Screw is a classic example of an unreliable narrator and perhaps one of the most popular. Henry James’ 1898 horror novella has a kind of three-fold narration at play. The primary narrator, the author, recounts to the readers the tale of a Christmas Eve gathering where he and his friends sit by a fire telling ghost stories. He tells us what he has learned from his friend, who provides the second layer of narration and who, in turn, is relating the bulk of the story as told in a manuscript by the third narrator. The manuscript itself is a relating of events from many years earlier. This third narrator, a governess who remains significantly unnamed, was hired by a man to look after his young niece and nephew. Of course, this leaves the whole story swirling in doubt and anxiety. Is the governess really seeing ghosts? Or, she is just a disturbed woman who should never have been left in charge of two young children? The genius of it is that there are so many possibilities, each of them equally terrifying, and this uncertainty leaves the readers fervently hoping for the truth of supernatural goings-on.

Also Read: The 15 Best Horror Books of the Last Decade (2010-2020)

11. Invisible Monsters–Chuck Palahniuk (1999)

Going into a Chuck Palahniuk novel, all bets are off except for the complete and utter certainty that you cannot trust the narrator. Instead of the more popular Fight Club, I chose to go with Invisible Monsters, which was rejected as too dark. Invisible Monsters is filled with booze, painkillers, and a whole lot of drugs. The narrator, Shannon McFarland, is left horribly disfigured in a set of bizarre incidents involving a mysterious shootout, a road accident and birds, among other things. She loses her jaw, her modelling career, fiancé, home and even her voice. She must learn how to live and speak again. In her speech therapy group, desperately needing someone to save and reinvent her, she meets Brandy Alexander. Brandy gives her a fresh start, a clean slate, and new and better lives offered up as the truth. Eventually, this landscape of lies and broken dreams threatens to fall apart.

That’s about the entirety of the story, but that’s not even covering one-quarter of the plot. Shannon’s first-person conspiratorial tone only holds readers at arm’s length. There are dizzying twists and turns and a whole lot more of the plot that cannot be summarised; the readers pick up piecemeal the secrets and the story as we jump from chapter to chapter, confused and bewildered as we follow this once-beautiful now-monstrous woman who avoids facing the facts till the end.

12. Pale Fire–Vladimir Nabokov (1962)

Vladimir Nabokov’s 1962 novel, Pale Fire, has four distinct sections. The first is the Foreword by Charles Kinbote, who claims to be a scholar from the country of Zembla. The second section is the poem called Pale Fire and divided into four cantos. The third and longest section is Kinbote’s commentary on the poem. The final section is an index in which Kinbote provides brief descriptions of the people and places mentioned in the text of the poem and his own commentary.

One does not read Pale Fire so much as one solves it. John Shade’s poem was his last, written before his murder. If Kinbote’s account is to be trusted, he was charged with the publication of the manuscript of Shade’s autobiographical poem. But any claim he has as a reliable purveyor of events is subverted immediately when, in the Foreword itself, Kinbote recounts the many reservations of Shade’s widow and friends with his handling of the poet’s last major work. Shade’s poem seems little more than a personal reminiscing. However, Kinbote co-opts Shade’s poem in his commentary, which transforms each line into the dazzling and labyrinthine story of the overthrow of the last king of Zembla, Charles II.

13. We Need to Talk About Kevin–Lionel Shriver (2003)

Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin is about a fictional school massacre. Kevin, a teenager who nurses violent tendencies, has lured, trapped and shot classmates and school workers before the novel begins, which plays out in the epistolary format, with Kevin’s mother, Eva, writing long letters to her husband, Franklin. Eva is torn between blaming her nurture and upbringing of Kevin and his inherent evil nature.

She and Franklin are partly estranged because they are constantly at odds when it comes to Kevin, with Franklin believing she is cold and ambivalent towards him. Eva, on the other hand, thinks Franklin is being duped by Kevin when he thinks his son is merely a sullen child. This adds to the novel’s sense of dread and ambiguity, with readers never really sure if Eva is muddled and if the signs of Kevin’s malevolence and hostility as she describes were exaggerated in retrospect. Despite Kevin’s unspeakably horrific crimes, neither Eva nor we (the readers) is ever sure if we judged Kevin accurately and remain utterly transfixed and haunted by it.

Also Read: 20 Most Anxiety-Inducing Movies of the 2010s Decade

14. Drood–Dan Simmons (2009)

Dan Simmons has written, and with great success, in a wide variety of genres. Drood is his foray into the historical novel. It is a fictional retelling of the final five years of Charles Dickens’ life, narrated by Dickens’ friend, foe, collaborator and competitor, Wilkie Collins. In Collins, Simmons creates a truly remarkable unreliable narrator. The readers question his motives from the very beginning. Collins proves to be less-than-reliable not just due to his severe laudanum addiction but also because of the smatterings of jealousy he harbours towards the more successful and celebrated Dickens. And yet, he is never truly unlikeable. The reader cannot root for him but is enthralled by him. Simmons thrusts his readers into a 700-page journey through a world of depravity and debauchery, and our guide and anchor is a man nursing an increasingly worsening opium addiction. Simmons manages at all times to endear him to us. Collins sinks deeper into addiction, disorienting us and leaving us unsure as to how much is real, a figment of imagination or a hallucination.

15. Lolita–Vladimir Nabokov (1955)

Putting Nabokov on the list twice might be cheating, but Humbert Humbert remains the undisputed king of unreliable narrators, so much so that he has duped the publishing industry into believing Lolita is a love story, that the twelve-year-old Dolores seduced HH deliberately. Like Pale Fire, Lolita has several layers of narration by different narrators. HH narrates from jail, where he is awaiting trial. The plot of Lolita is well known: Humbert Humbert is obsessed with Dolores Haze. He marries her mother, eventually kidnaps Dolores, and begins a sexually abusive relationship with her. All throughout, Humbert tries to explain his love for the underage Dolores as simply unconventional and hardly criminal.

Nabokov is such a writer that readers often fall prey to Humbert’s justification. Humbert’s unreliability is exposed in the gap between his account of events and how any rational reader would interpret them. This linguistic gap is where the lie takes place: Humbert hardly hides plot points. He only softens his transgressions – accident instead of murder, love instead of abuse. The reader can see this friction as clear as daylight. It’s only Humbert who never identifies his sins and remains in a constant state of damnation. His unreliability as the narrator serves to identify the flaws in his logic and his morals.