A century ago, one of the greatest literary movements flourished in the West – Modernism. For starters, here are the ten best works of modernist literature to explore.

As the tremors of World War I reverberated through the early 20th century, and the ground beneath civilization shifted with the weight of rapid social and technological advancements, a literary earthquake erupted. This explosion of creativity, christened Modernism, wasn’t just a tremor in the literary landscape; it was a tectonic shift, a complete rearrangement of the narrative plates upon which stories were built. The comforting Victorian facades of linear plots and neatly contained characters crumbled, replaced by a dizzying landscape of fractured timelines, unreliable narrators, and audacious explorations of the most unsettling recesses of the human experience.

The weight of history, the anxieties of a changing world, and the ever-present spectre of mortality cast long shadows upon the narratives produced in this era. Yet, amidst the darkness, glimmers of beauty and resilience shine through. We witness the redemptive power of art, the solace found in human connection, and the unrelenting human spirit searching for meaning even in the face of absurdity. Stream-of-consciousness narratives dance between past and present, challenging linear chronology and embracing the fluidity of human thought. Language itself becomes a malleable instrument, bent and twisted to reflect the complexities of the modern experience.

Through fragmented syntax, multiple perspectives, and polyphonic voices, modernist works shatter the traditional structures of storytelling, demanding active engagement and participation from the reader. In this article, we explore 10 of the greatest works of modernist literature. Read on to have your literary landscape fundamentally changed forever.

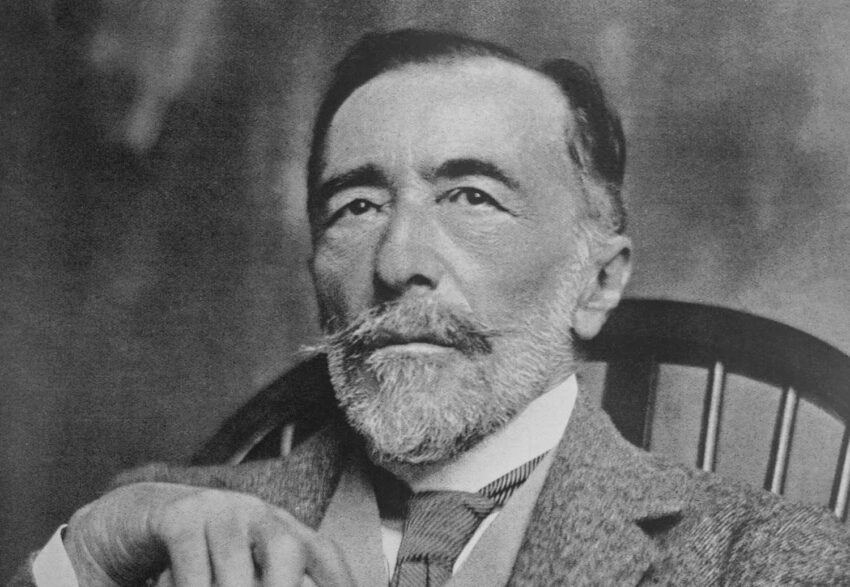

- 1. Heart of Darkness (1899) – Joseph Conrad

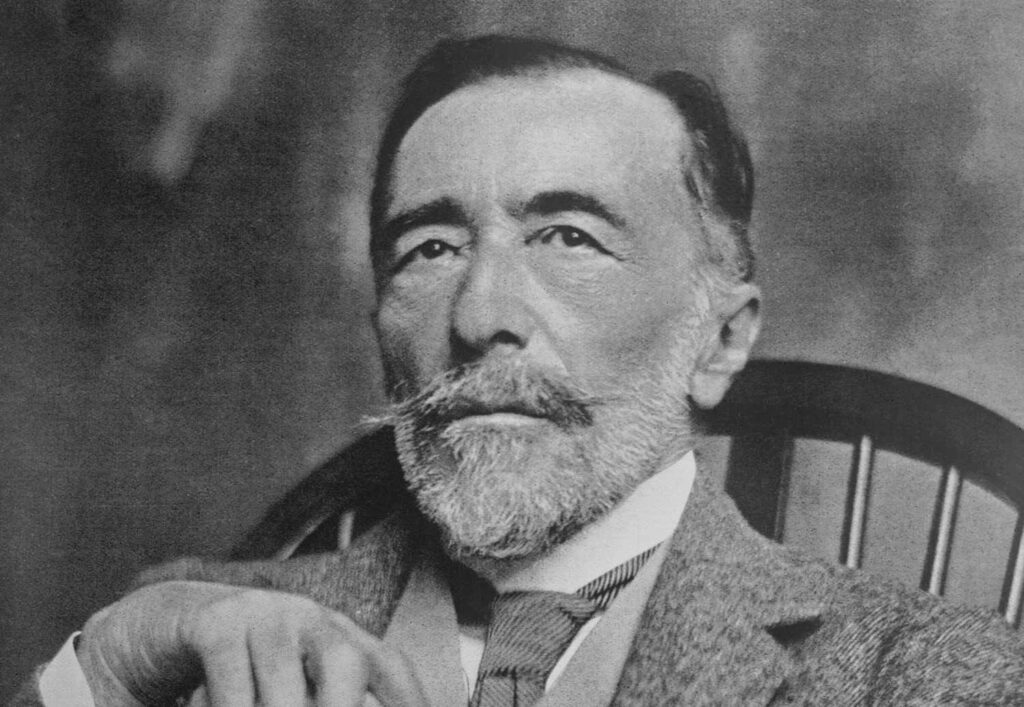

- 2. Mrs Dalloway (1925) by Virginia Woolf

- 3. Ulysses (1922) by James Joyce

- 4. The Waste Land (1922) by T.S. Eliot

- 5. The Great Gatsby (1925) by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- 6. The Counterfeiters (1925) by André Gide

- 7. In Search of Lost Time (1913-1927) by Marcel Proust

- 8. The Sound and the Fury (1929) by William Faulkner

- 9. A Farewell to Arms (1929) by Ernest Hemingway

- 10. Waiting for Godot (1952) by Samuel Beckett

1. Heart of Darkness (1899) – Joseph Conrad

In Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, we embark on a journey, not just the literal riverboat voyage up the Congo, but a descent into the depths of human nature. Charles Marlow, our seasoned sailor-narrator, spins a chilling yarn to fellow Thames-bound travelers, recounting his quest for Kurtz, an ivory trader with a mythical reputation. The narrative structure is fragmented, mirroring the disorienting jungle itself. Time blurs, reality bleeds into dreams, and Marlow grapples with unreliable memories and shifting perspectives. This stream-of-consciousness style plunges us headfirst into his moral quandaries as he witnesses the brutal exploitation of the Congolese by the European ivory company.

The darkness Conrad paints isn’t just the physical Africa, thick with humidity and primal menace. It’s the encroaching darkness within Kurtz, who has succumbed to the allure of absolute power and become a demigod to the natives. Initially drawn to Kurtz’s enigmatic brilliance, Marlow becomes increasingly horrified by his descent into savagery. He grapples with his own capacity for brutality, the thin line between civilization and the “heart of darkness” lurking within every human. Colonialism’s brutal reality forms the backdrop of this psychological odyssey, but Heart of Darkness is more than a damning indictment of colonialism. The novella forces us to confront the unsettling truth that the potential for barbarity resides within us all and that the veneer of civilization is fragile.

2. Mrs Dalloway (1925) by Virginia Woolf

Stepping into Mrs Dalloway is like stepping into a bustling London street on a single day in June 1923. Virginia Woolf’s masterpiece isn’t about grand plots or sweeping adventures but the symphony of thoughts and moments that make up one woman’s ordinary, extraordinary life. Clarissa Dalloway, our protagonist, flits through her day like a butterfly, her consciousness flitting between memories, anxieties, and preparations for a grand party that evening. We’re privy to her inner monologue, a stream of consciousness that dips and dives, revealing regrets, desires, and a keen awareness of the fleeting nature of time.

Woolf’s modernist brilliance lies in her innovative storytelling techniques. Time stretches and compresses, past and present bleed into one another, and the narrative shifts focus like a sunbeam bouncing through a crowded room. We hear not just Clarissa’s voice but those of people she encounters throughout the day: a young couple honeymooning, a shell-shocked veteran struggling with his demons, and a working-class woman harboring resentment towards Clarissa’s privileged life. Despite their disparate lives, these characters are all connected by the invisible threads of the city, their paths tangentially brushing against Clarissa’s as she buys flowers, visits doctors, and navigates the social swirl of pre-party preparations. Through Clarissa’s lens, we see the fragility of life, the weight of memories, and the constant negotiation between societal expectations and our own desires.

3. Ulysses (1922) by James Joyce

Plunge into Dublin, 1904. Not the postcard tourist version, but the gritty, vibrant belly of the city, captured in James Joyce’s monumental modernist novel, Ulysses. It’s not a journey for the faint of heart but a labyrinthine exploration of human consciousness, myth, and the very fabric of existence. Leopold Bloom, our unlikely hero, is an ordinary advertising canvasser. Yet, through Joyce’s complex literary lens, his day becomes an epic odyssey. We shadow Bloom as he navigates the mundane (buying breakfast kidney, attending a funeral, etc) and the extraordinary (encountering a Cyclops-like figure, witnessing a brothel’s bawdy secrets).

Joyce explodes traditional storytelling. The narrative fractures, mirrors Bloom’s stream-of-consciousness, and throws us into a whirlwind of puns, parodies, and linguistic acrobatics. One chapter mimics Homer’s epic style, another parodies a newspaper, while another streamlines language into musical notations. It’s a symphony of voices, a celebration of the messy, vibrant cacophony of human life. But beneath the dazzling wordplay lies a profound exploration of human experiences. Bloom grapples with grief, jealousy, and the yearning for connection. He searches for his spiritual son in Stephen Dedalus, a young intellectual disillusioned with his artistic ambitions. Their paths, like Odysseus and Telemachus, intertwine and diverge, mirroring the universal themes of fatherhood, mentorship, and the search for meaning.

Ulysses is more than just a novel; it’s a cultural touchstone. As a demanding yet exhilarating text, it has immense rewards in store for the patient reader. Back in the 1920s, it challenged the boundaries of literature, paving the way for generations of modernist writers. It’s also a love letter to Dublin, a tale woven with its history, myths, and everyday eccentricities.

4. The Waste Land (1922) by T.S. Eliot

T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land dives deep into the shattered psyche of a post-war world, where hope has withered and civilization crumbles like dry leaves. Published in 1922, it became a defining text of modernism, a genre that broke free from traditional forms and embraced fragmentation, ambiguity, and the raw power of language. Elio’s “wasteland” isn’t a physical desert, but a spiritual one. It’s a landscape of broken promises, disillusionment, and the hollowness that echoes after the Great War. The poem fragments like shattered glass, mirroring the fractured psyche of its characters and the world they inhabit. We shift through time and space, sifting ancient myths and Biblical references from the gritty streets of London and the arid plains of the Holy Land.

There’s no clear narrative, no hero to guide us. Instead, we encounter a kaleidoscope of voices, whispers from the past and cries from the present. A bored socialite laments her empty life, a fortune teller spouts cryptic pronouncements, and a pub singer croons a bawdy song. Each fragment, like a shard of broken glass, reflects a different facet of human experience, the beauty and ugliness, the joy and despair, all woven together into a tapestry of loss. Eliot’s language is a weapon, sharp and unforgiving. He wields puns, allusions, and fractured syntax, creating a dense, multilayered text that demands active participation from the reader. The Waste Land is not a poem to be just passively consumed, but one that challenges and provokes, forcing us to confront the darkness within ourselves and the world around us.

Also Read: Explore the World: A Literary Walk Through London in 10 Books

5. The Great Gatsby (1925) by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby shimmers like the green light seen by the titular character across the bay – a mesmerizing beacon of unattainable dreams and tragic illusions. Set in the Roaring Twenties, a time of unbridled extravagance amidst the anxieties of a changing world, the novel delves into the lives of those chasing shadows under the New York sun. Jay Gatsby, an enigmatic millionaire with a mysterious past, throws lavish parties at his opulent West Egg mansion. We’re drawn into his orbit through the eyes of Nick Carraway, a young Midwesterner drawn to the East Coast’s glittering promise. Gatsby’s parties are a whirlwind of jazz music, flowing champagne, and glittering flappers, a desperate attempt to reunite with his lost love, the captivating Daisy Buchanan.

Daisy, Nick’s cousin, resides across the bay in the wealthy enclave of East Egg. Married to the arrogant and uncaring Tom Buchanan, she embodies the emptiness of the upper class, their lives a hollow dance of privilege and boredom. Gatsby’s relentless pursuit of Daisy fuels the novel’s tragic narrative, a collision of yearning and class divides. Fitzgerald’s prose is both lyrical and deceptively simple. He captures the era’s opulence and emotional undercurrents with masterful precision. We feel the scorching heat of Long Island summers, the intoxicating allure of Gatsby’s parties, and the gnawing disillusionment beneath the surface of extravagant lives.

6. The Counterfeiters (1925) by André Gide

André Gide’s 1925 novel The Counterfeiters takes us on a journey into the heart of forgery and self-discovery, blurring the lines between truth and illusion, creation and deception. The novel delves into the life of Édouard, a middle-aged writer grappling with creative paralysis and existential angst. Édouard’s world is turned upside down when he encounters Bernard, a charming con artist who specializes in forging banknotes. Bernard’s effortless duplicity awakens a dark fascination in Édouard, who begins to question the very foundations of his identity and his art. Is his writing, his carefully crafted persona, anything more than a sophisticated form of forgery?

The novel’s structure cleverly mirrors Édouard’s internal turmoil. The narrative shifts perspectives, blurs timeframes, and incorporates fictional stories within the larger story, creating a labyrinthine effect that reflects the protagonist’s own confusion. We’re never quite sure what’s real and what’s fabricated, mirroring Édouard’s struggle to distinguish between his authentic self and the masks he wears for the world. As he delves deeper into the world of counterfeiting, he encounters a cast of intriguing characters, each reflecting a different facet of his internal conflict. There’s Olivier, the intellectual friend who grapples with the limitations of reason, and Laura, the seductive yet enigmatic woman who embodies the allure of the unknown. Through these encounters, Édouard is forced to confront his demons and grapple with the uncomfortable truths about himself.

7. In Search of Lost Time (1913-1927) by Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, also translated as Remembrance of Things Past, is a monumental masterpiece of Modernism, a sprawling yet intricate tapestry woven from the threads of memory, loss, and the elusive nature of time. Published in seven volumes between 1913 and 1927, it follows the unnamed narrator as he delves into the recesses of his past, resurrecting lost moments and grappling with the bittersweet passage of time. The novel begins with a simple act: the taste of a madeleine dipped in tea. This seemingly trivial experience triggers a cascade of memories, transporting the narrator back to his childhood in Combray, where the scent of lime blossoms and the sound of the church bells once again fill his senses.

But Proust’s memories are not merely nostalgic snapshots; they are portals to a lost world, shimmering with an almost unbearable intensity. Through the narrator’s introspective gaze, we encounter a vibrant cast of characters: the aristocratic Swann family, whose intricate social relationships become microcosms of a changing world; the enigmatic Charles Morel, whose musical genius masks a tormented soul; and Albertine, the object of the narrator’s obsessive love, whose elusive essence becomes a symbol of the fleeting nature of desire. Despite its melancholy undertones, In Search of Lost Time is not a tale of despair. Through his relentless pursuit of the past, the narrator discovers the redemptive power of art. He finds solace in the act of writing, in the meticulous reconstruction of lost moments, and in the creation of a timeless universe where beauty and sorrow intertwine.

8. The Sound and the Fury (1929) by William Faulkner

With intricate narrative arcs woven through fragmented consciousness, William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury takes readers on a dizzying journey into the crumbling world of the Compson family, a once-aristocratic Southern clan grappling with loss, decay, and the haunting shadows of the past. Published in 1929, the novel stands as a titan of modernist literature, challenging traditional storytelling with its innovative form and unflinching exploration of the human condition. Faulkner plunges us into the narrative through the shifting perspectives of three Compson sons – Benjy, Quentin, and Jason. Caddy, the enigmatic daughter at the heart of the story, becomes a symbol of lost innocence and unfulfilled desires, her choices haunting the lives of her brothers.

Benjy, intellectually disabled and trapped in an eternal present, experiences the world through a kaleidoscope of senses, his fragmented thoughts forming a stream-of-consciousness tapestry of sights, sounds, and smells. Quentin, tormented by his sister Caddy’s departure and grappling with existential angst, jumps through time, weaving memories and philosophical ruminations into a tragic narrative of isolation and despair. Jason, the pragmatist and businessman, represents the cold, calculating face of modernity, fixated on material gain and devoid of the emotional depths of his brothers. Through these disparate voices, we piece together the tragedy of the Compson family. As the narrative unfolds, Faulkner masterfully exposes the complexities of family dynamics, the burden of history, and the agonizing struggle for identity in a changing world.

9. A Farewell to Arms (1929) by Ernest Hemingway

In Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, we enter the trenches of World War I not with booming cannons but with a quiet intimacy. Frederick Henry, an American ambulance driver, narrates in his characteristic clipped prose a tale of love, loss, and disillusionment against the backdrop of brutal conflict. Hemingway paints a stark landscape, not of grand heroism but of mud, exhaustion, and the constant threat of death. Henry finds solace in his love for Catherine Barkley, a British nurse serving amidst the chaos. Their romance blossoms with a gentle urgency, fueled by the fleeting nature of life under constant threat. They steal moments of happiness: whispered conversations in darkened hallways, passionate encounters against the backdrop of war.

But Hemingway never romanticizes the battlefield. The violence lingers; a pervasive darkness that threatens their fragile love story. The narrative, like Henry’s emotions, ebbs and flows. Hemingway masterfully shifts between moments of tender lyricism and stark realism, portraying both the beauty of human connection and the brutality of war. The ending of A Farewell to Arms is as stark as the novel itself. The lovers reunite, but their world is irrevocably shattered. Loss casts its heavy weight, leaving Henry adrift in a changed landscape, physically and emotionally scarred. Yet, even in the face of devastation, there’s still the unflinching flicker of hope.

10. Waiting for Godot (1952) by Samuel Beckett

On a barren stage, under a bleak sky, Vladimir and Estragon wait. Not for the bus, not for their lunch, but for Godot, a mysterious entity who never arrives. Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot is a masterpiece of modernist theatre, a play that gleefully strips away conventionality and plunges us into the absurdity of existence. Beckett’s world is one of circular conversations, forgotten hats, and existential quandaries. Vladimir and Estragon, a mismatched pair defined by their dependence on each other, fill the void with meaningless chatter, silly games, and philosophical musings. They grapple with time, its agonizingly slow passage punctuated by sudden bouts of urgency. Are they waiting for salvation, for meaning, or just for something, anything, to break the monotony?

The play itself is a puzzle, defying traditional linear narratives. Time bends and loops, past and present blur, and characters appear and disappear like mirages. Pozzo and Lucky, a master-slave duo, arrive like a jarring interlude, only to vanish into the void once more. Godot, the omnipresent yet absent entity, looms like a tantalizing mystery, forever just out of reach. Beckett’s genius lies in his ability to evoke laughter and despair in equal measure. The comedy is absurdist, born from the characters’ futile endeavors and nonsensical exchanges. Yet, beneath the humor lurks a profound sense of existential dread. The waiting becomes a metaphor for life itself, a constant quest for meaning in a universe indifferent to our struggles.

Also Read: Understanding How Form is Content in ‘Waiting for Godot’