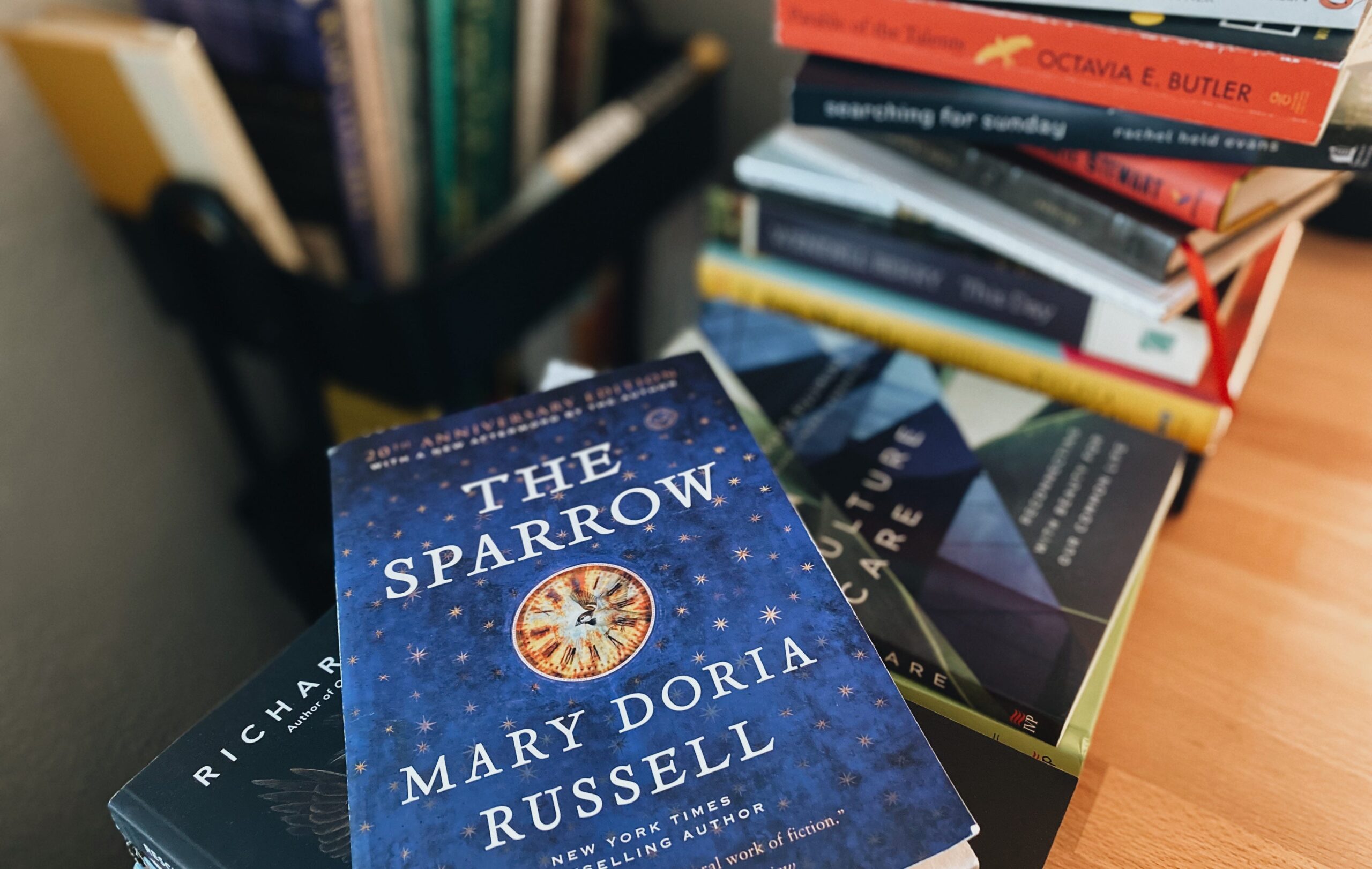

Learn more about Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow (1996), one of the best sci-fi (?) books that will leave all generations fascinated below!

To begin with: the question of genre. Labelling a book one genre or the other goes a long way towards setting reader expectations. There are presumptions associated with certain genres. Mary Doria Russell’s first book, The Sparrow (1996) won the Arthur C. Clarke Award, James Tiptree Jr. Award, Kurd-Laßwitz-Preis and the British Science Fiction Association Award in the years following its release. These are awards given to science-fiction and fantasy books, and they unequivocally categorise The Sparrow as a book of the sci-fi genre. This poses a minor hitch. The Sparrow is relatively light on the science of sci-fi. Technology is only a wrapping for investigations into theology. The Sparrow is fascinated by other questions, hence its unique approach.

Premise of The Sparrow (1996)

In 2019, the SETI program at Arecibo Observatory discovers the not-so-distant alien world of Rakhat in the vicinity of Alpha Centauri. A strange singing emanates from this planet, signalling that it is not only inhabited by intelligent life but one that could perhaps communicate with humans since humans themselves can emulate the sounds of their songs. Driven only by these melodies, a Jesuit-backed mission is launched into the yawning jaws of space. On the team is the main character Father Emilio Sandoz, a priest and a talented linguist, steadfast in his faith that he is chosen by god to lead humanity in this first contact with aliens. The other members are his friends and co-workers, people who coincidentally have the exact skills required to pilot the mission. On Rakhat, the missionaries encounter the Runa and the Jana’ata–two genetically unrelated bipedal humanoid species. For the missionaries, the glowing success of the mission and the mirrored selves of humanity are signs of god’s wonderful creation. This is the secondary timeline, taking place in the past.

The primary timeline takes place in what is the novel’s present, the year 2060. The mission that began with such promise has reached a catastrophic conclusion. Only Father Sandoz survived. He is returned to Earth and sequestered away by the crumbling Jesuit order to recover, report, and if need be, repent. Popular outrage directed by a mischaracterized report by the United Nations has shattered the Jesuit order and turned public opinion against Sandoz. Sandoz was rescued half-dead and three-quarters stark raving mad. The manner of his rescue further humiliated the Jesuits. He was found imprisoned in a brothel; he is also a murderer. Much of the blame for the mission’s failure falls on Emilio. All the church wants is a confession. All Emilio wants is to be left alone to die, to take his secrets and shame, his damaged faith and body into the grave. Between these two narratives, we learn how the mission to Rakhat came to be in the first place, and what went right before taking a turn for the worse. We see Emilio recover physically, and grapple with questions of his faith. And finally, we follow the Father General of the Jesuit as he assembles a panel for Emilio’s confession in their attempt to discover the truth.

Picking up The Sparrow with only the premise in mind is a strange experience. What are we to expect of a book about a first contact mission backed by the Vatican? What would such a mission resemble–a religious mission and not a military excursion–knowing the dubious nature of religious excursions to new lands even here on Earth? The barebones of this review is this: The Sparrow is a beautiful book and it can be read in several different ways, most of which will be determined by what our expectations were when we began reading. For some, it will be a literary meditation on spirituality that asks questions about faith, religion, god and that old chestnut “Why do bad things happen to good people?” For others, it is a character-driven drama. No matter what you find in the book, there are ideas here that cannot be distilled into soundbites without losing their essence.

Search for Meaning in The Sparrow (1996)

Somewhere along the way, the struggle and search for meaning becomes Emilio’s god, somewhat like the golden calf of the Israelites, worshipped briefly and fearfully when faced with the divine. In his life before the twisted events of first contact, was Emilio truly content as he would have us believe? Or was his search for meaning a struggle for his life to mean something else, something more than a rough-hewn boy from the slums of Puerto Rico finding refuge in the church? This inner restlessness that drives him to look for evidence of god everywhere, is it a sign of contentment? For proof of his faith, he launches himself into the stars, following the great tradition of humans looking up at space and seeing it brimming with the possibility of escape, of meaning.

Consider Emilio’s celibacy. He is celibate with the express purpose of turning his energies wholly towards god, hoping that his personal struggle is part of a greater struggle for meaning. Emilio subordinates all else before god based on a promise of something greater to be realised in the future. For him, god’s presence was strengthened by an absence. Between time present and time future, the celibate Emilio hopes there will be compensation for the virtue of chastity and denial, that there will be a subsequent reward. In fact, what is sex if not maximising the present? If not imposing the self through its pleasure onto ephemeral moments? Self-denial is another way of assuaging his spiritual lack. All his life, Emilio has compensated for it through excellence. This space mission he sees as final proof. God is real because he gives Emilio personally an inherent meaning and significance in his life. God points and says, you my son are special. God proves his existence by showing himself to Emilio as a sign.

Also Read: Should Children Read Non-Fiction Books?

Divine Providence

For Emilio and his crew, divine providence was a serious presumption for the basis of interstellar travel. Compare this to Europeans sailing into the unknown with nothing but absolute faith in god and their superiority–the church has not come very far from that. The missionaries go ahead as though willed by god. Their strange reality becomes the assurance of God’s blessings. When the push comes to shove, the will of god turns monstrous by design. God’s face is revealed as hideous in their personal register because they find themselves reduced to nothing by the same endeavour they were so convinced was taking place because Deus Vult, god wills it so. He has led them to their downfall and gave no aid in their time of need. God and meaning are reduced to symbols of personal significance. There are grave injustices littering the everyday. And yet, despite that Emilio finds god is real. Naturally, he breaks with god when things fall apart for him, only when he specifically must endure a particularly dark night of the soul.

This leads us to an important point. Providence and presence are found only in retrospect. In the narration and re-narration of events after they have already manifested, Emilio finds significance, and stitches meaning from disparate strands. Since the story itself puts so much emphasis on revelation, it’s necessary to remember that revelation comes only in retreading, not in events as they unfold. Consider the narrative architecture: a single story explained from two separate points in a timeline converging at the same destination. Again, it heightens the aspect of providence. The sections are in conversation with each other and the reader. Upon re-treading that same narrative ground, we notice new meanings.

An Act of Translation

Translation is an invention of meaning, not solely linguistic but also socio-cultural meaning. Emilio’s linguistic talents are essentially instrumentalised in his search for meaning in symbols and signs. And language fails him in times of great need. He finds himself made insignificant when he cannot mediate between alien beings. When he himself is insignificant, that can only mean that god’s nature is monstrous. He was god’s best beloved after all. His encounter with the aliens only points to an irreconcilable gap. This gap exists in the first place, however, because Emilio conflates personal significance as proof of universality.

The true nature of the alien songs is a gut-wrenching twist far more brutal than any of the physical and psychological damage inflicted on the missionaries. A breakdown of communication that takes place between the few surviving missionaries is another example of how the book views translation. Emilio, who can only read French and has never learnt to speak it, can barely make sense of what his companion says to him. It is at this moment the absurdity of their entire endeavour catches up with him: in the narcissism of their belief, they aimed for the stars, hoping to make themselves understood. They carried their wretchedly human and limited understanding into an alien world. Of course, they failed.

The Invisible Hand of God

As readers make their way past the logistics of the mission falling perfectly into place, one can’t help but be reminded of Deus Ex Machina–god from the machine–in its predictability. But this predictability is of utmost importance. Is this absurd predictability a sign of divine providence making itself known through a series of coincidences? Is it possible that Emilio befriended the exact people needed to undertake the mission utterly unaided by god? It is here that the seemingly predictable plot becomes noticeable. The narrative is formulaic, the aliens only a few colourful frills away from humans, a first contact that more resembles Europeans disembarking on the shores of the New World than the discovery of the first intelligent extraterrestrial species.

The book can frustrate readers with these apparent failings. Nevertheless, it is a text worth engaging with for the issues it raises and how it answers them. The generic tendencies of science fiction are repurposed to serve the ideas of theology. Why can’t faith be examined on Earth, you ask? Because the Earth is insufficient. It has been drained dry of meaning. Free will, after all, is meant to be exercised to either move closer to god or farther away. But so far in space, in such a recklessly planned mission that hinges more on gut feeling than scientific temperament, and to have the complex nitty-gritties of space travel succeed despite its implausibility, and then and only then to have everything taken from you, it will damage the strongest foundations.

The Risk of Belief

No belief is without risk. The question of risk and recklessness ties into other key preoccupations of the novel. Emilio, over the long days and nights of the mission, falls in love. And yet he gives it up as a sacrifice to god. Emilio then finds his belief treated much like Cain’s. His sacrifice is insufficient, like Cain’s offering of the fruits of the soil. Abel, who gave a bloody offering of his flock, was accepted, which was enough. Emilio Sandoz, once a candidate for canonization, a man drunk on god and married to the church, was his sacrifice of so little value? This risk of scorn is present even in love, which is a kind of belief after all. God’s love, unconditional and without end, is meant to protect. To be vulnerable and open, to put yourself in harm’s way to be toyed with or loved, with nothing but god’s guarantee–this is a terrifying risk. In the gap between the question of faith and its answer, all eternity is contained, all regrets, doubts, and joyous anticipation.

Why You Should Read The Sparrow (1996)

The Sparrow is an accomplished novel, with every layer revealing joy and sorrow in equal parts. It moves slowly, with little action or fights, and builds towards its shattering conclusion through elaborate deliberations on the nature of faith, of personal experience of god, and on what drives us towards morality and goodness outside religion. The book is neither pro- nor anti-religion but remains perfectly balanced, anchored by top-tier character work. There are true believers, sceptics, and atheists aplenty. The question is not to prove or disprove the presence of god. The question, rather, is how we could possibly accommodate faith in moments of catastrophe, when the believer is farthest from god, or when god’s love is farthest from them. Mary Doria Russell’s prose is fantastic. Her characters are easy and fleshed out, speaking in drawls and quips, bawdy jokes and pop-culture references. They are all lunatics in love. But the doom that hangs over their heads is inescapable and inevitable. There are no twists and shocking revelations, despite Emilio’s confession being the central node around which the narrative is structured. Enough is foreshadowed for readers to pick up, such that the moment when the truth is revealed is not exploitative misery but rather a necessary naming, to see a thing for what it is–personal experiences, no matter how traumatic, do not go a long way to disprove god’s existence universally. Naming a thing weakens the hold it has over the soul. The “what” was never in question. The important thing is always “where to now?”