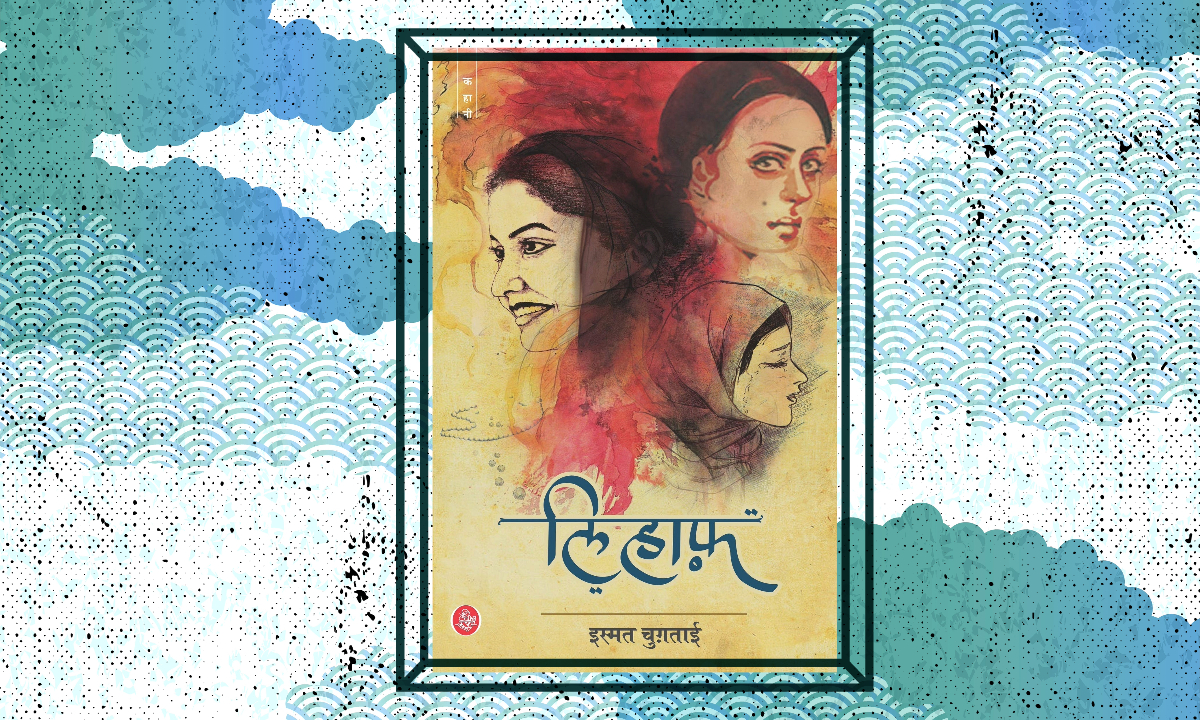

Lihaaf (Ismat Chughtai) bears queer connotations, and this essay shall look into the politics of repression and violence that it seeks to question and explore.

Lihaaf (Ismat Chughtai) entered the circle of Indian literature in 1942 when it was published in a literary magazine in Lahore called Adab-i-Latif. The story has earned a reputation for its forwardness and undaunting expression. However, the story’s fearlessness brought along a series of court hearings for Chughtai, wherein the writer held her ground by fighting instead of apologizing and accepting charges of obscenity against her work.

Lihaaf chronicles the life of Begum Jan (her failed marriage and the closeted desires of her and her husband), Rabu, and her niece. We get a picture of the atmosphere of Begam Jan’s haveli through the memories and eyes of her unnamed niece as we flit back and forth in the narrative and find out about the sexual relationship between Begum and her maid.

In this essay, I explore how Lihaaf, on the surface level, is an ahead-of-time exposé of homoerotic relationships since it is brave enough to question the existing social norm around gender and sexuality. Besides, I shall also dive into how the objective of the story is not to explore homosexuality but critically attack the power dynamics that alter the meaning of sexual exploitation and sexual independence by making them interchangeable.

Before moving forward, let us learn a little about Ismat Chughtai herself.

About Ismat Chughtai

Ismat Chughtai (21 August 1915 -24 October 1991) is one of the most celebrated and recognized voices in the Urdu Literary canon. Her contributions to the field are held in the same esteem as Saadat Hassan Manto, another of the most prominent figures of Urdu Literature. She explores themes of female sexuality, communal violence, and partition; her writings belong to the realist tradition and seek to criticize society by highlighting the parity between different counterparts of the same society – the rich and poor, male and female, and so on.

Chughtai paints the world with a compassionate but critical tone; her stories have inspired generations of writers and have been a source of comfort to women who find themselves in her characters. The first novella by Chughtai was Ziddi (1941), although her short stories like Khudai Khidmatgar were already part of the public reading domain in 1935. Along with being a gifted author, Chughtai was a screenwriter and filmmaker, her first filmmaking project as a producer being Sone ki Chidiya (1958). Her immense talent made her worthy of many awards, including the Padma Shri that the Government of India awarded her in 1976. She also won the Makhdoom Literary Award, Andhra Pradesh Urdu Akademi Award in 1979, and the Rajasthan Urdu Akademi Award in 1990.

Also Read: How Feminist Retellings are Quickly Shaping our Understanding of Myths

Subdued Pedophilia in Lihaaf

Paedophilia is a word attributed to define sexual feelings or desires toward children, Lihaaf, in a sense, is a treatise of sexual violence and transgression directed towards the young by adults (by Begum and her husband). The narrative is not solely about Begum’s loneliness, ennui, and sexual curiosity, even less about the journey of sexual exploration; it is more about sexual exploitation and how Begum violates a little girl by trying to entice her with expensive clothes and other delicacies. Chughtai warns us of paedophilia from the very beginning by highlighting how Begum’s husband was fond of young and slender boys.

“Nawab Saheb had contempt for such disgusting sports. He kept an open house for students—young, fair and slender-waisted boys whose expenses were borne by him”.

The imagery in the form of shadows in Lihaaf is used to portray the sexual encounter between Rabu and Begum. This imagery is a precursor to what is later revealed in the narrative – the assault Begum unleashes on her niece (the narrator). Instead of floral imagery, which is very common in the writings of Chughtai, we witness the shadow of an animal (“Begum’s quilt was swaying like an elephant”). An elephant is not a tender beast; it is terrifying enough for the little girl to cover herself up to avoid the beastly shadow created by Rabu and her aunt. This is precisely how the narrator envisions her aunt, a fierce, dark, and horrific presence, a fiend that feeds people smaller (with less agency) than her.

Both Begum and her husband, despite the difference in their stature in household politics, have things in common – They both suffer from a sense of acute sexual repression. The husband undergoes sexual repression because of the evident taboo that is associated with his desires, and the wife because of the lack of her husband’s touch, which transforms into aggression and obsession by the end of the narrative. Both husband and wife give voice to this repression by violating the voiceless.

The hierarchy of exploitation is established by the husband of Begum at the top (he is the cause of Begum’s suffering and unrequited sexual desires), followed by Begum and the others. However, through the character of Begum Jan, we see how the oppressed can be the oppressor, since instead of checking her predatory desires, the same desires that his husband supposedly harnesses to inflict pain on young boys, she replicates her husband’s pattern and inflicts incorrigible scars on the psyche of her niece, whom she took in her ‘care’ when the mother of the child was away.

Irretrievable and Irremediable Scars of Sexual Violence

Despite the anonymity of the narration, the fact that the story is told by Begum Jan’s niece is evidence enough that what we are witnessing is the story of the narrator. She is retelling events of the past in the form of a story but the memory of these incidents never quite left her. We, as the readers, are witnessing a time-lapse, the starting point of it is the incident of abuse, and the end of it is the memory of that abuse. We are unaware of the extent of the abuse, the events following the abuse, or what happens to the victim after the incident of abuse. Since the narrator talks about the incident with disgust and fear, it is enough to help the readers understand how trauma takes the shape of memory and memory shapes trauma in return.

In Lihaaf, the readers garner evidence of the traumatic legacy of the incidents talked about by the narratology (referring to the pattern in which the story is structured) of the narrative. One key aspect of traumatic narration is the evident breaks in between the action of the narrative, which we also call a lack of linearity, which we can see in the form of the narrator jumping backwards and forwards from the timeline of the action (action being the assault). Another important aspect that sets documentation trauma is circularity (dodging the issue or deterred response to it) in which the victim approaches the incident (something like the narration of Beloved by Toni Morrison), for instance, we are made aware of the present the first thing in the narrative, and then we get to know about Begum, her husband, Rabu, the other aspects of the household, including the mutual and consensual sexual relationship between Rabu and Begum, but the actual issue is addressed later and that too not very explicitly.

Nevertheless, the documentation of trauma is the only way to pronounce it and give substance to it; henceforth, the acknowledgment of the pain makes Lihaaf a timeless tale. Overlooking this aspect of the story would not only keep us away from what Chughtai’s vision was but also exhibit how ignorant we are towards the forces presently active in society and chooses to ignore the signs of sexual violence if we are not affected by them personally. Many young victims of abuse talk about the inability to address these issues because of the inherent notion that no one would believe in what they are saying. This is probably something that happens to the narrator as well; we know that she is retelling her own story but are unaware as to whether she has narrated these incidents to anyone else in her family. In her story, Chugtai depicts child abuse by highlighting something that seems hidden, something that is omnipresent but never talked about or explored in common parlance. This is a testament to the brilliance of her writing, wherein what she wanted to tell us is always there but simultaneously not there if we don’t want to look at it or acknowledge it.

Another layer of the story is that of Begum being a victim herself, a victim of the patriarchal system that corners female desires. The irrevocable question here, withstanding everything that Begum herself witnesses, is whether something as inexcusable as violating somebody else’s body without consent can be excused and does the fact that she herself was a victim gives her the right to oppress someone else or is it the very same thing that makes her the flag bearer of the same patriarchal oppression that ruined her own life, and, if so, is there any way of breaking away from this cycle of abuse and the recurring structure of exploitation? Chughtai leaves us with all these questions to explore questions that, just like her story, are timeless and pressing even in the world that we inhabit today.

From the Same Author: Panopticon and Female Surveillance in Margret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale