Let’s dive into the diverse and dark examination of a not-so-little life in Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life in the review below.

In the heart of the bustling concrete jungle that is New York City, four friends, all graduates of the same university, find their lives entwined in a symphony of joy and sorrow. From being published to finding itself shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2015, A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara is crafted to unveil a tapestry of human existence through an endearing and diverse crew — broke, adrift and buoyed only by their friendship and ambition. There is the kind, handsome Willem, an aspiring actor; JB, a quick-witted photographer and painter pursuing fame in the art world; Malcolm, a frustrated architect at a prominent firm; and withdrawn, brilliant, enigmatic Jude.

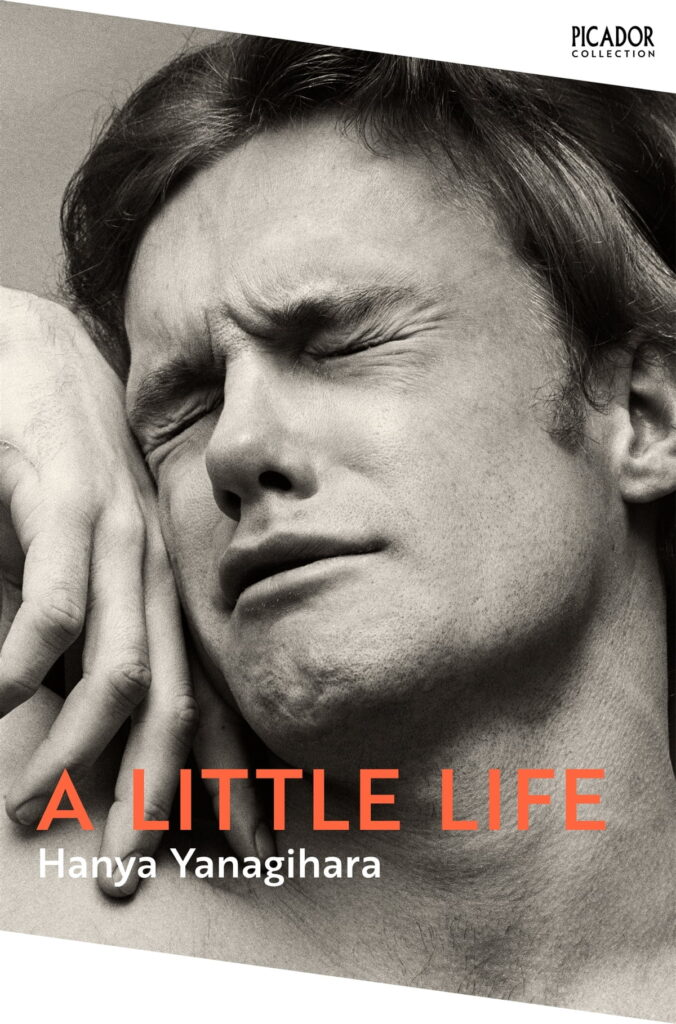

As the quartet navigate the labyrinthine terrain of life, their bonds become compasses, directing and redirecting them amid the tempestuous uncertainties of existence. While they manage to stay afloat, love flourishes, dreams are nurtured, and aspirations soar in defiance of life’s unforgiving trials. Yet, over the decades, their relationships deepen and darken, tinged by addiction, success and pride. However, their greatest challenge, each comes to realise, is Jude himself — a fierce litigator by profession and a shy, nurturing friend, gentle to all but himself.

A Little Life is a vivid brushstroke of emotions diverse and deep — on the page and the heart. It is a dark and harrowing examination of a not-so-little life, laying bare the beauty and the ugliness behind it — all emerging from the crucible of pain, experience and memory.

Time Will Tell, in its Passage Handled Well

A Little Life is not heavy on plot for a book of its length. Instead, the novel’s nuances come from its intense look into the psyches of Willem, JB, Malcolm and Jude— in all their relationships— with people, professions, and themselves. In short, things that make the ordinariness of any life extraordinary. And we follow this unravelling of their stories through decades. But as the novel progresses, we realise that Yanagihara has more than a conventional Bildungsroman on her mind. For one, she certainly handles the narrative passage of time well. What we learn of the characters is often through the interlacing of flashbacks within the narrative present. This swinging back and forth in time helps us make sense of the fears and motivations that drive the characters we have come to know and grown to love.

Eventually, as the novel progresses, Jude, the mysterious one of the four, comes to the fore. A part of the story’s dramatic effect and suspense is owed to the uncertainty around Jude’s character. What we get are little details and foreshadowings until the reality of Jude’s abusive, dismal past solidifies into a gut-wrenching portrait of him in our minds. Heavily guarded, fiercely disciplined and endlessly vigilant, Jude hides many secrets about his life from his closest friends and loved ones. Jude’s insistent inconspicuousness about his life earns him an epithet from JB, who says, in one of his quips:

We never see him with anyone, we don’t know what race he is, we don’t know anything about him. Post-sexual, post-racial, post-past. The post-man. Jude the Postman.

The reader will not have to conjecture like JB for long. We eventually will witness Jude’s unfolding as the pain of his past cuts through his body (quite literally) and his carefully constructed life.

A Mosaic of Love and Friendship

However, interspaced between moments of darkness are tender little moments of joy— found not in grand gestures but rather in mundane moments of affection brought by the familiarity of quiet understanding. The book’s length could perhaps be ascribed to the fact that it relies on these moments of love and friendship to make the rest of the unbearable, bearable.

Despite his self-imposed limitations, which is a manifestation of his trauma, an essential truth that Jude perhaps comes to understand, however untimely, is that:

All of the most terrifying Ifs involve people. All the good ones do as well.

And despite his efforts, Jude struggles. Nevertheless, if anything, it is the people in his life, particularly his relationship with Willem, that offer him solace and offer us invaluable meditations on love and friendship. As someone who had been friendless during the formative years of his life, there is an instance within the book where we hear Jude’s profound advice to a lonely child, which we realise is inspired to him by his friendships with Willem, JB and Malcolm:

The only trick of friendship, I think, is to find people who are better than you are— not smarter, not cooler, but kinder, and more generous, and more forgiving— and then to appreciate them for what they can teach you, and to try to listen to them when they tell you something about yourself, no matter how bad — or good — it might be, and to trust them, which is the hardest thing of all. But the best, as well.

Love may or may not be a saving grace. But this book does not wholly present it as one. There is some truth in Yanagihara refusing Jude to overcome his past solely with the help of other people. Through the novel’s haunting cries for redemption, it explores how love may restore and renew but not necessarily repair.

Witnessing an Agonised Mind

A Little Life is an uneven and unrelenting chronicle of an anguished mind. “An elegant mind wants elegant endings”, remarks Jude, while explaining to his friends that he loves Mathematics because it offers the possibility of “a wholly provable, unshakeable absolute in a constructed world with very few unshakable absolutes.” And later, during one of the lowest points in his life, flung between life and death, it is his favourite axiom that Jude recalls— the axiom of equality:

The axiom of equality states that x always equals x: it assumes that if you have a conceptual thing named x, that it must always be equivalent to itself, that it has a uniqueness about it, that it is in possession of something so irreducible that we must assume it absolutely, unchangeably equivalent to itself for all time, that its very elementalness can never be altered. But it is impossible to prove…Not everyone liked the axiom of equality…but he had always appreciated how elusive it was, how the beauty of the equation itself would always be frustrated by the attempts to prove it. It was the kind of axiom that could drive you mad, that could consume you, that could easily become an entire life.

To read A Little Life is to become painfully aware of Jude’s dangerous devotion to the axiom of equality.

Why Should You Read A Little Life?

Through A Little Life, Yanagihara has masterfully crafted a story drenched in unforgettable observations of the human psyche in all its ebbs and flows. As with anything, it might have its shortcomings, but not among them is a failure to evoke emotions through its poignant examination of the marks humans leave on one another.

The book is a literary journey through the intricate tapestry of existence, a reminder that even amid darkness, there exists within the human spirit the ability to create beauty, forge bonds, and find meaning in the most unexpected places and — despite A Little Life being heart rendering — in the most unexpected of stories. But like Jude observes, ‘What in life wasn’t connected to some greater, sadder story?‘