10 Most Adapted Sherlock Holmes Stories: Sherlock Holmes, the great detective, is not the first detective of this genre; that honor is reserved for Edgar Allan Poe’s Le Chevalier C. Auguste Dupin, who combined his intelligence with a speck of imagination, almost supplanting himself into the minds of the criminals. Arthur Conan Doyle took the more grounded route of crafting Holmes as the individual who utilizes his exceptional observational skills and fiercely logical mind to capture criminals and solve crimes outside the traditional norm and out of the grasp of Scotland Yard’s investigative prowess. Within Doyle’s creation of Holmes are also shades of Emile Gaboriau’s Monsieur Lecoq. While both these characters (Dupin and LeCoq) laid the groundwork for the detective genre, Holmes emerged as a burst of lightning, a character fully developed with his own brand of individualism and arrogance. He is not averse to maligning his progenitors within the stories themselves, as he does in A Study in Scarlet when Dr Watson compares him to Dupin, calling Dupin an “inferior fellow”. Doyle’s stories have now become synonymous with the detective literary canon; the conventions and plot devices of the detective stories can be traced back to Doyle’s Holmes and, to a certain extent, Agatha Christie’s Poirot stories. His deduction methodology is so popular that it has almost taken over the vernacular, even though the procedure that Holmes uses is called abduction – the logical inference of the simplest results from observations.

All these, with the iconography and the symbolism – be it the long pipe, the deerstalker hat, the long gaunt face animated in the middle of an investigation, while prickly and haggard when bored, and a penchant for the Bohemian lifestyle and a proclivity for the theatrical – have made Holmes the subject of over 250 adaptations.

This list will give you an insight into the 10 most adapted Sherlock Holmes stories. On investigation, this writer has found striking patterns as to which stories have been popular enough through the ages to those which have been adapted and referenced again and again, fidelity to the source material notwithstanding. This list will explore the longevity and popularity of these ten stories in particular while suggesting the best adaptations for you to watch.

Note: To streamline this list, the short films and silent films pre-Basil Rathbone era haven’t been considered because of the difficulty in acquiring these films to watch. There are also some notable omissions in this list because, according to this writer, some adaptations miss out on the reason why the story needed to be adapted in the first place. One of those examples would be ‘The Musgrave Ritual’. Adapted eight times, every adaptation misses the key element of the story being one of Holmes’ earliest cases. The entire story is structured as a frame tale – Watson provided the introduction while Holmes recorded and recounted the case. The story is centered around Holmes investigating the case without the help of his trusted soundboard, which would certainly make for an otherwise exciting adaptation.

-

Table of Contents

- A Scandal in Bohemia

- A Study in Scarlet

- The Adventure of the Dying Detective

- The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton

- The Bruce-Partington Plans & The Naval Treaty

- The Adventure of the Six Napoleons

- The Adventure of the Speckled Band

- The Final Problem

- The Sign of Four

- The Hound of The Baskervilles

A Scandal in Bohemia

One of the most famous of Sherlock Holmes stories, this one comes with the added distinction of being one of the least adapted stories. That is primarily because, as a story, it follows the same pattern of Holmes being asked to investigate and acquire some incriminating photographs for the then Prince of Germany from socialite and adventurer Irene Adler. Holmes manages to identify that the photograph is in Adler’s possession by utilizing disguises and mingling with the stable lads, finally managing to locate where the photograph has been hidden. But what makes the mystery so tantalizing is even after all this rigmarole, the mystery doesn’t resolve in the conventional pattern but ultimately breaks it, and that is primarily due to the character of Irene Adler.

Doyle wasn’t the most dexterous at writing female characters. Even in A Scandal in Bohemia, the character of Adler isn’t well explored beyond the contents of the letter and the effect it has on Holmes being thwarted by her. However, Irene Adler is lightning in a bottle – a woman who bested the greatest detective of all time in his own game and shares a cleverness and ability to conjure the kind of disguises that Holmes donned. Holmes’ admiration for her in calling her “The Woman”, then, could be construed as one pertaining to romance, which tonnes of pastiches, direct-to-video films, and even adaptations of A Scandal in Bohemia choose to focus more on.

As scandalous as it may read, it is hard-pressed to find a good adaptation of Adler as a character focusing on the single-line blurb – the only woman who could ever beat Sherlock Holmes. In their rendition of Sherlock, Sherlock (2010 – 2017), Stephen Moffat and Mark Gatiss depict Irene Adler as a dominatrix and a subordinate of Jim Moriarty. Here, she is depicted as the polar opposite of Doyle’s version – a criminal and someone serving a high-end clientele. While she displays an intense attraction to Sherlock, it is later revealed to be a ruse when Adler identifies as queer. Unlike Doyle’s story, Sherlock consistently manages to foil Adler’s plans. On the other hand, the CBS series, Elementary, presents one of the more unique wrinkles in the canonization of Irene Adler, revealing that Adler is Jamie Moriarty, Holmes’ unseen nemesis through most of the second season. She had created the Adler persona to seduce Holmes and fake her death so that Holmes would be distracted and unable to uncover her crimes. While Elementary would never be called one of the best adaptations of Sherlock Holmes, it did manage to introduce some unique changes in the characters. In the case of Irene Adler, this unique swing works.

-

A Study in Scarlet

The one that started it all, A Study in Scarlet, is the definition of a lopsided story. Divided very noticeably into two parts, the first half explores the first time Dr John Watson meets Mr Sherlock Holmes and agrees to move into his place in a rent-sharing capacity. We find Holmes using his detection powers to investigate the murder of a woman at a suburban home, beginning with the understanding of the clue left behind as a ploy to foil the police investigation. While the murderer continues to evade the investigators, the story travels back in time to the salt plains of Utah and among the Mormons, recounting the story of Joseph Ferrier and his daughter to successfully join the dots around this crime.

The first act of the first half of A Study in Scarlet is arguably one of the most referenced elements in all of Sherlock Holmes adaptations, primarily because it recounts the meeting between the two iconic characters, Holmes’ deduction skills, the description of his methodology, his obsession with cigarette ashes, and Watson’s genuine befuddlement at Homes’ intellect. The story is also extremely fast-paced in how it introduces the case, the players, the supporting cast, and how Holmes solves the case. However, Conan Doyle’s massive digression towards the end is so distinct and removed from the entire case that most adaptations would avoid the backstory segment altogether, punching in another case or changing Hope’s backstory to completely avoid trudging through those waters. Part of the reason is also Doyle’s representation of Mormon culture, which is inaccurate and exaggerated, to tell the least.

Also, Read – Victorian England Through the Eyes of Sherlock Holmes and Dr John Watson

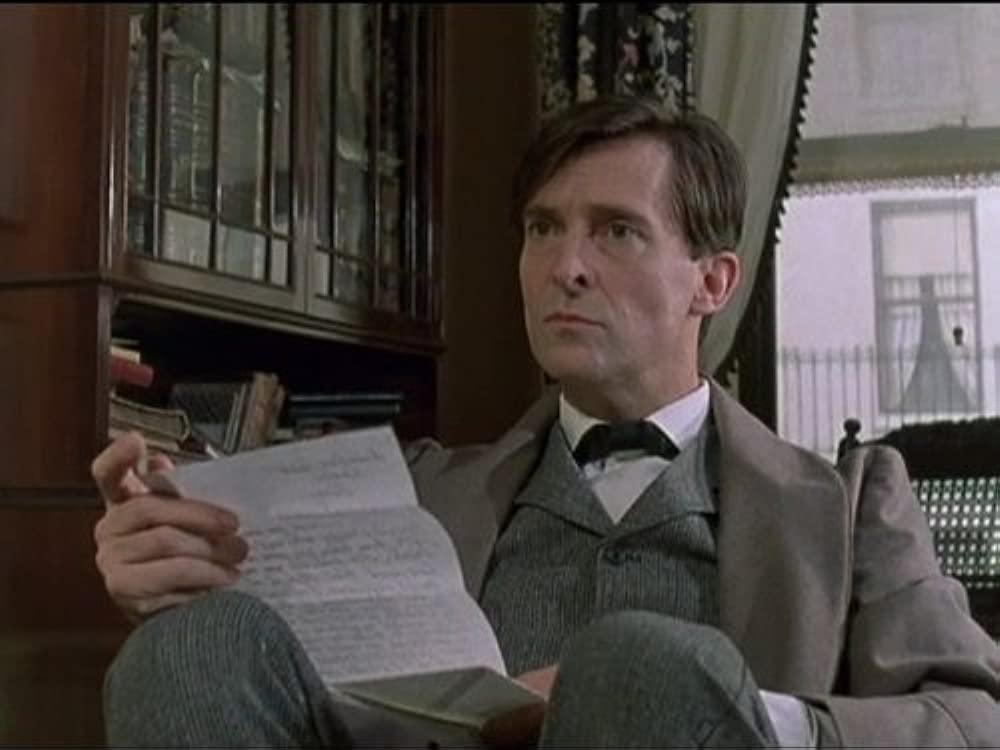

A Study in Scarlet has been adapted for television a total of four times, and it is one of the most notable omissions in the Granada adaptations of the Sherlock Holmes stories. However, the 1979 Soviet adaptation titled The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson is one of the more faithful adaptations. The meeting of Holmes and Watson has been adapted in the first episode along with an adaptation of The Speckled Band, and it works primarily because of the individual performances and chemistry between Vasily Lyanov as Sherlock Holmes and Vitaly Solomin as Dr Watson. Its fidelity towards the source material, along with the painstaking recreation of the Victorian era by that production team, is especially astounding. The actual case of A Study in Scarlet, or the Jefferson Hope case, is adapted in the second episode of this series. On the other hand, the pilot episode of the BBC’s Sherlock series, titled ‘A Study in Pink,’ is remarkable in how much it faithfully adapts the core plot elements of A Study in Scarlet but manages to almost drag it to the modern era, subverting very specific elements of the original story’s plot as a pointed homage to fans of the series while ensuring that the story moves at a rollicking pace.

-

The Adventure of the Dying Detective

This story follows a bedridden Holmes who is averse to being treated by his friend Dr John Watson and instructs his friend to bring in Mr Culverton Smith as the only person with the foreknowledge to cure him. What we learn as the story progresses is that deliberately infecting Holmes with Tapanauli Fever had been Smith’s plan all along, while Holmes’ infirmity had all been a ploy for Culverton Smith to reveal his plan.

Iconography is essential; so is a twist in the tale in which the story’s hero is out of action from the beginning. Doyle’s description of the haggard Holmes, bedridden by the disease, does that two-fold job of hammering home the effects of this disease while focusing on Holmes’ commitment to solving a case by hook or by crook, even if it meant starving himself for over three days and risking alienation from his closest friend. Further, a study would prove that the most popular Holmes adaptations always focused on stories with unique moments in Holmes’ career, making the case in which Holmes is almost dying the second most adapted Sherlock Holmes story of all time.

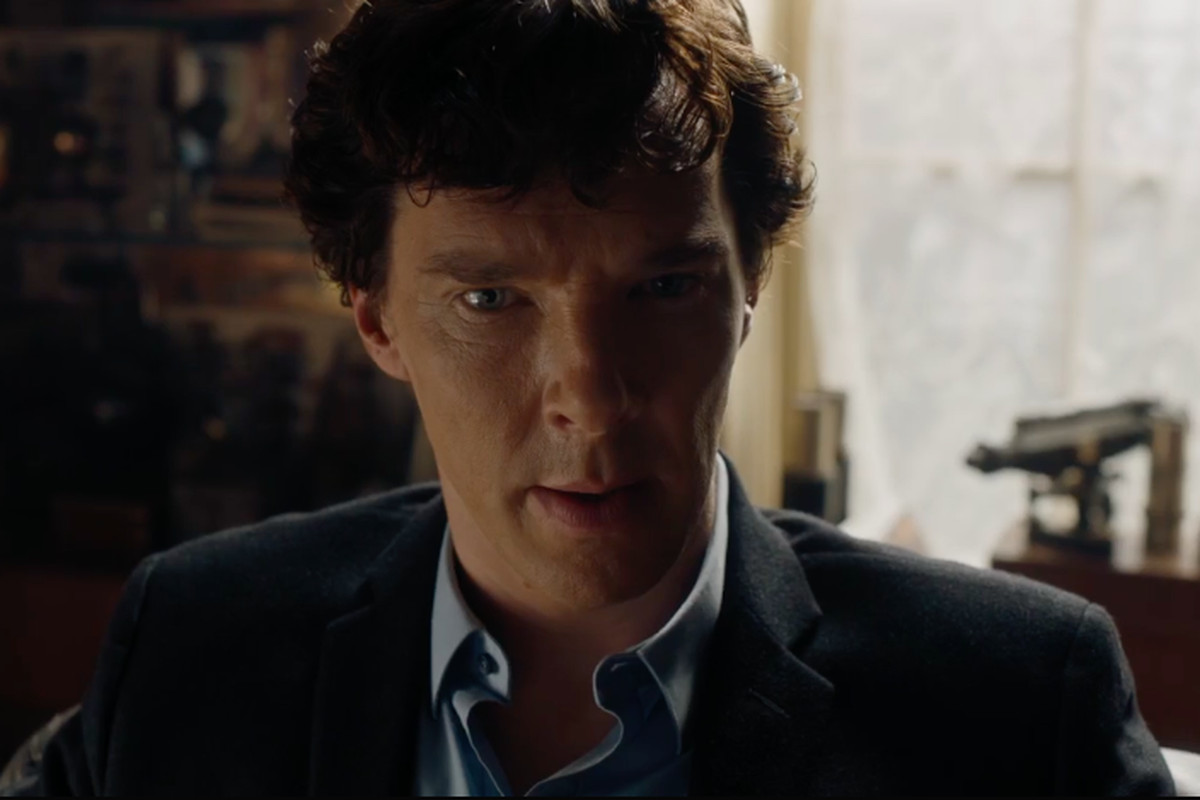

The Dying Detective has been adapted five times for television, with the most faithful adaptation being Granada Television’s treatment of the episode by the same name, starring Jeremy Brett as Sherlock Holmes, Edward Hardwicke as Dr John Watson, and Jonathan Hyde as Culverton Smith. The second notable adaptation is from Sherlock, a show notorious for not directly adapting the story but introducing different elements to push the sensibilities of the storytelling to modern times while keeping the soul of the story intact. Mark Gatiss and Stephen Moffatt adapt this story in the show’s fourth season as ‘The Lying Detective’. In this version, Culverton Smith is shown to be a wealthy philanthropist and a serial killer, while Benedict Cumberbatch plays an infirm and delirious Sherlock. Their interactions induce a healthy dose of tension in the narrative, eschewing the predictability of the original storyline.

-

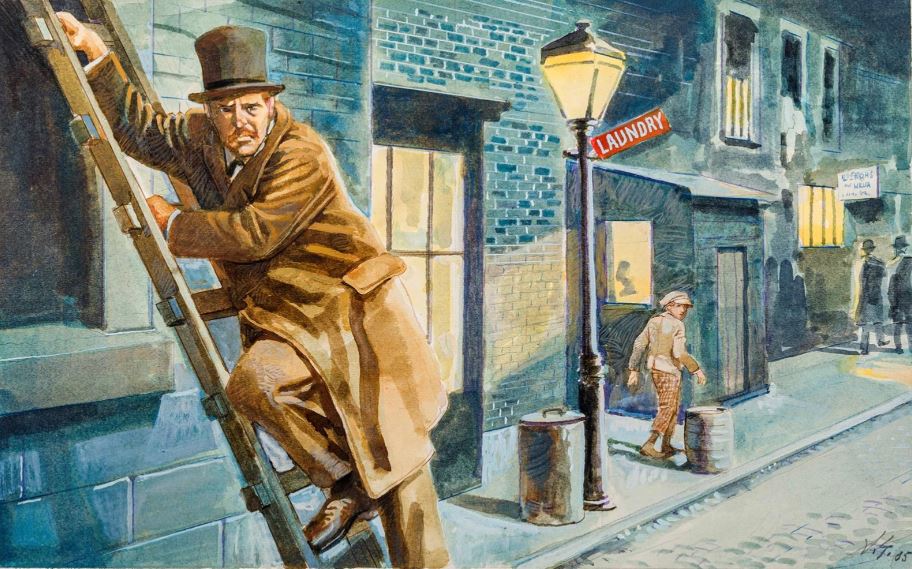

The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton

The story follows Holmes being hired by the debutante Lady Eva Blackwell to retrieve compromising letters from Charles Augustus Milverton in exchange for 7000 pounds. But Milverton refuses, and Holmes and Watson resolve to burgle Milverton’s house, with Holmes going so far as to don a disguise and romance Milverton’s housemaid at the expense of learning about the layout of Milverton’s manor. Unlike most stories, Holmes and Watson can neither stop an unlikely visitor nor are they interested in bringing her justice.

The story is almost a personification of the act of blackmail. Blackmail as a concept – the prospect of earning money or earning status or privilege by leveraging secretive information from the person belonging to the higher status quo – has been one of the most prevalent cases which literary detectives have been challenged with. Through the pulpy narrative, Doyle chooses to explore the human condition, almost acting as a bystander to the events occurring, as Milverton falls to his hubris and not by Holmes’ intelligence or deduction skills. These are interesting wrinkles that could have made this story a remarkable one to adapt, though the faithfulness of the adaptations is always debatable. These are some of the very few stories in the Holmes canon where Holmes is uninterested in bringing the results of the case to the light of the law because, for him, death is already justice earned.

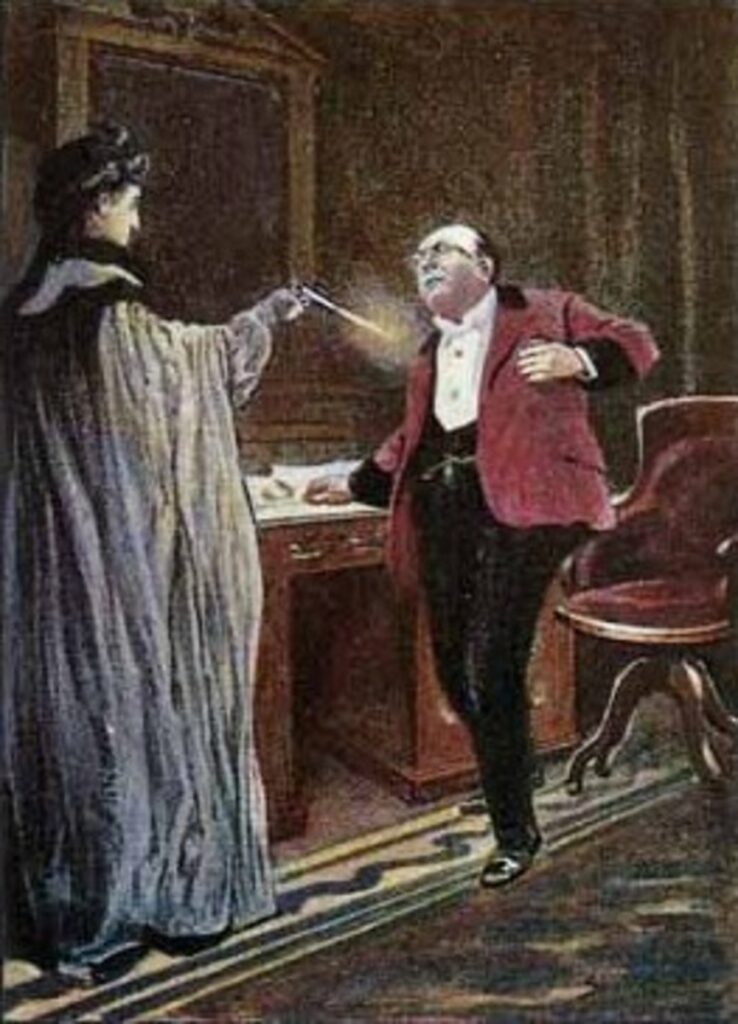

The Adventures of Charles Augustus Milverton has been loosely adapted as the film The Missing Rembrandt while being adapted four times on television. The Granada Television adaptation starring Jeremy Brett as Holmes has a feature-length episode, ‘The Master Blackmailer’, with Robert Hardy playing the eponymous blackmailer. The role is catnip for actors, so the stories are adapted to give the character more space than the short story allowed. Thus Hardy’s version of Milverton has a larger presence in the story, even though his face isn’t revealed until the very end. The episode’s end deviates from the source material in that Holmes is almost haunted by the death of Milverton and the lengths to which human beings can be pushed due to strife. That is why he requests Watson to not chronicle the story, a far cry from the original story, where Milverton’s death was treated more cavalierly. In contrast, the Season 3 finale of BBC’s Sherlock, ‘His Last Vow’, stands out. In it, Sherlock’s ‘mind palace’ finally meets its match when his opponent manages to construct his own “mind palace”, hatching a battle of wits to a literal physical arena. Besides, Lars Mikkelsen’s portrayal of Charles Augustus Magnussen is remarkable in that he completely transcends Andrew Scott’s portrayal of Jim Moriarty and becomes a fantastic villain of his own.

-

The Bruce-Partington Plans & The Naval Treaty

Part of the collection of stories titled His Last Bow, which chronicled the final adventures of Sherlock Holmes, The Bruce-Partington Plans belongs to a quadrilogy of stories dealing with espionage (The Naval Treaty, The Bruce-Partington Plans, The Second Stain, and His Last Bow). When the Bruce-Partington Plans were first published in the pages of the Strand Magazine in December 1908, the first great war was still five years away. One of the more fascinating stories from the perspective of adaptation, Sherlock Holmes is requested by his brother Mycroft Holmes to investigate the theft of top-secret submarine designs. As Holmes and Watson navigate through their investigation, they learn that the papers were stolen to be dispatched to a known ‘foreign’ agent because the specifications of the plans of the submarine would be a prized possession for any country locked in this battle of espionage.

The popularity of the Bruce-Partington plans lies in what the stories represent. By the first decade of the 20th century, dreadnought-class battleships were leading the arms race, but research was being conducted on submarines and torpedoes. It was also believed that Germany had been conducting espionage on an unprecedented scale. It can be argued that Doyle isn’t breaking the story structure of the traditional detective novel but introducing elements of espionage through high stakes, with characters known to the victims responsible for the theft, as international espionage boils over and brings the country to the brink of a great war. As a result, the stories feel ripe for adaptation because there is a sense that the stakes are automatically raised higher when the objects, or MacGuffins, are intricately linked with national security.

Both The Naval Treaty and the Bruce-Partington Plans have been adapted six times on television. However, most adaptations prefer punching the two stories together and exploring a composite story dealing with espionage as its core element. ‘The Twentieth Century Approaches,’ the final episode of the Soviet-produced television movie titled Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson adapted the espionage quadrilogy in almost an anthology format, with the setting shifting to World War II. It works by uniting the four stories under a common theme and a moody atmosphere of war-torn England; those movies had the added distinction of being extremely faithful to the original stories, and this is no different. The second adaptation that stands out is Granada Television’s adaptation of The Naval Treaty, starring Jeremy Brett as Sherlock Holmes, because of its fidelity to the source material and, of course, Brett’s performance. Finally, the Season 1 finale of BBC’s Sherlock, titled ‘The Great Game,’ is a race against time where Sherlock and Watson must solve a series of unconnected mysteries at the behest of a bomber, who would set off an explosion in one part of London if the cases weren’t solved. It includes the premise of both stories in its plot.

Also, Read: The Popularity of Sherlock Holmes

-

The Adventure of the Six Napoleons

The Six Napoleons refer to six Napoleon busts, and the case referred to Sherlock Holmes by Inspector Lestrade is unique precisely because of its quirk. By the time Holmes and Watson started investigating, mysterious burglaries had occurred in which three of these six busts had been broken. While Lestrade believes that the burglar is a Napoleon hater, Holmes isn’t convinced, as all of the Napoleon busts come from the same mould. The case finally takes a turn when the fourth bust is found destroyed, and a murder takes place.

The Adventure of the Six Napoleons is one of those cases where Arthur Conan Doyle takes the basic structure of another of his short stories and tweaks it to perfect it. This story shares remarkable similarities with The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle in terms of the basic structure. Still, the former is also very popular because it is one of those quintessential Holmes mysteries which feature the mafia, murder, and the idea of greed being the motivating factor. This is also the story where Holmes’ brilliance is finally acknowledged by Scotland Yard in a beautifully moving and memorable speech by Inspector Lestrade. This would also be the last time Lestrade made an appearance in any of the Conan Doyle novels.

While the Granada Television adaptations could be safely attributed to the story’s widespread popularity, The Adventure of the Six Napoleons has been adapted eight times: twice in film and six times on television. One of the best adaptations is the 1944 Sherlock Holmes film Pearl of Death, starring Basil Rathbone as Holmes and Nigel Bruce as Watson. While not a direct adaptation and more of a substrate on which a far more pulpy story takes place, Pearl of Death works because it is a race against time, with Holmes and Watson already knowing what they are looking for. The film also interestingly manages to make Holmes feel vulnerable and fallible, and the entire movie is also a method for Holmes to search for redemption by solving this case.

-

The Adventure of the Speckled Band

Regarded as one of Arthur Conan Doyle’s finest stories featuring Sherlock Holmes, The Adventure of the Speckled Band follows young heiress Helen Stoner, who comes to Holmes and Watson in fear that her stepfather threatens her life, Dr. Grimesby Roylott. Holmes and Watson visit the family estate of Stoke Moran, and a spine-chilling, (snake) biting mystery unfolds thereafter.

The first instance that makes The Speckled Band an instant classic is its sense of atmosphere and gothic underpinnings – be it the presence of a dilapidated and decaying manor or a brutish, almost demonic, antagonist. The supernatural undercurrent as a result of these elements is juxtaposed perfectly with Holmes’ extremely logical deduction of these events, but the brutality and coldly calculated nature of the murder shake Holmes to the core, where he remarks to Watson how doctors if given to crime, could become the most dangerous of criminals. There is also the theme of parental conflict due to financial circumstances. But the Speckled Band is also marred by Doyle’s conflation of Indian culture with the sinister and exotic, a path he had already undertaken to a greater and much more critical degree in The Sign of Four.

The Adventure of the Speckled Band has been adapted a total of ten times – four times on film and six times on television. Notably, Conan Doyle himself wrote the first theatrical adaptation of this story. In the Granda adaptation of this story, Jeremy Brett’s almost exquisite performance as Sherlock Holmes parallels Jeremy Kemp’s terrifying and intimidating performance as Dr Grimesby Roylott. Other than Moriarty and even Milverton, Roylott might be one of the few Conan Doyle villains who manage to leave an impression in the reader’s mind.

-

The Final Problem

Arguably one of the top three Sherlock Holmes stories based on iconography alone, The Final Problem introduces Sherlock Holmes’ arch-nemesis in a decidedly explosive fashion. Holmes arrives at Watson’s residence one evening after escaping three murder attempts that whole day. It isn’t a coincidence that those attempts all took place after he met with Professor James Moriarty, who advised Holmes to stop seeking justice against him to prevent any regretful outcomes. As Holmes himself concedes, Moriarty is the great detective’s intellectual equal. Conan Doyle transports us to Switzerland, where Watson will be kept cleverly away from a sojourn between Holmes and Moriarty, leading to a fatal end.

Like Irene Adler, Professor James Moriarty came about as a plot device, a perfidious one since his introduction in The Napoleon of Crime came without any buildup. It is believed that the genesis of this character happened because of Doyle’s interest in finally killing the character of Sherlock Holmes. But the influence of Moriarty has expanded beyond the stories in the canon, with pastiches referencing Moriarty, expanding and revealing his shadowy tendrils among earlier cases of Holmes as well. Moriarty has also been part of other adaptations tangentially, not directly connected with Sherlock Holmes and the cases he was investigating. Because he is the only villain who managed to almost kill Holmes, his mystique and enduring appeal ensure that The Final Problem remains one of the most loved Sherlock Holmes stories across so many years.

The Final Problem and its variations have been adapted and presented on the screen a total of eleven times. There are also adaptations where the events of this story and The Empty House are punched together, which makes sense in the context that Holmes’ return is almost inevitable. Besides, the villain of the latter story is very closely connected to Moriarty, giving the overall story a sense of continuity. It is, however, ironic that the two best adaptations of the Moriarty character are not only different from each other but have significant deviations from Doyle’s creation as well. Guy Ritchie’s 2011 film Sherlock Holmes: The Game of Shadows uses The Final Problem as the bracketing story, with an original plot driving the narrative through. Jared Harris’ portrayal of Professor Moriarty felt very traditional and menacing until the final sequence at the opera house, where we see the both of them playing a mental chess game, imagining how their fisticuffs would ultimately end. Conversely, Andrew Scott’s portrayal of Jim Moriarty in BBC’s Sherlock is the epitome of a psychopathic genius. He truly embodies Conan Dyle’s literal interpretation of “both sides of the same coin”, and Scott’s portrayal of Moriarty manages to get under the skin of both Sherlock (Benedict Cumberbatch) and the audience, his genius solely focused on destroying Sherlock, even if it meant sacrificing his own life.

-

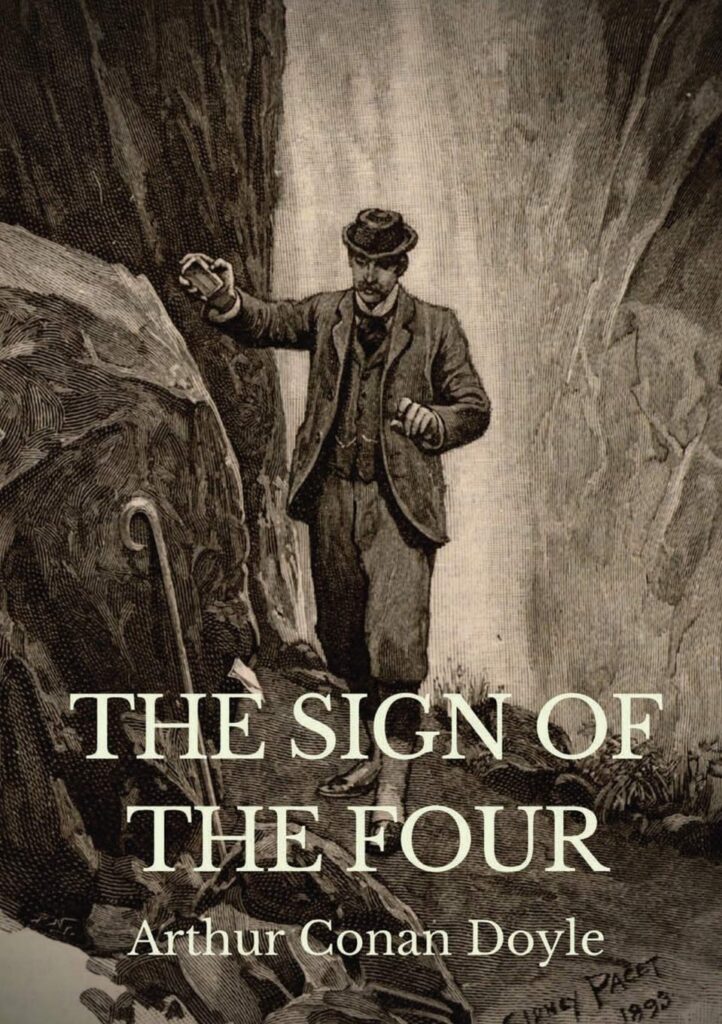

The Sign of Four

Also the second-most adapted story in the canon, this story opens with a young woman named Miss Mary Morstan asking Sherlock Holmes for assistance in figuring out her father’s inexplicable absence. Mary tells the story of how her father, Captain Morstan, disappeared ten years ago and how, ever since, she has been receiving a pearl every year after having answered an anonymous newspaper advertisement. She asks for Holmes’ help in discovering the real motives behind these mysterious gifts. As Holmes and Watson investigate, they get drawn into a complicated case featuring treasure, a one-legged man, poisoned darts, murder by said poisoned darts, a search for the perpetrator using a bloodhound named Toby, and, of course, the titular “Sign of Four” and how the organization came into being. Amidst all of this, there is a subplot developing concerning the romantic feelings Watson has for Miss Morstan.

While The Sign of Four gives us a Conan Doyle who has become better at juggling tonality and genres, its understanding of India is racist in how it exoticizes the subcontinent through the colonialist’s lens. Unfortunately, because the adventure-thriller genre lends itself well to adaptations easily, adapting this story, with its elements almost intact, has been common, albeit with subtle subversions. The second key indicator of the popularity of The Sign of Four is its importance within the canon. It is the first Holmes story that introduced the idea of Holmes’ use of cocaine when faced with existential ennui. While adaptations have tended to forget the caveat in Holmes’ drug use, it cannot be denied that the act shows Holmes in the light of an infallible but flawed hero. It is perhaps not surprising that the stories that have been mostly adapted are those that utilise Watson as a character with a substantial arc, and this story brings out Watson’s caring nature towards Holmes and his budding romantic life on the side. Last, but not the least, it is also tonally consistent for a direct adaptation.

This is the second most adapted of all Sherlock Holmes stories – 14 times. If, however, there is one adaptation that needs to be checked out to understand and enjoy The Sign of Four, pick out its 1983 adaptation. Filmed before Granada Television’s adaptation of Sherlock Holmes had been released, this is one of the two television films (the other one being The Hound of the Baskervilles) to be produced by Weintraub. This adaptation of the story indulges the gothic tendencies of the source material and features an additional murder, a fight on a merry-go-round hearkening back to Hitchcock’s Stranger on a Train (1951) and a chase through a hall of mirrors. Ian Richardson as Holmes is a more humane and physically capable version of the character, which is in tune with the extremely gothic and pulpy world the narrative sets itself in. Watson, too, is a much more intelligent character, less goofy than the Nigel Bruce iteration of the Basil Rathbone films. Further, it substitutes the romantic side-plot between Watson and Morstan with a focus on the friendship between Holmes and Watson.

-

The Hound of The Baskervilles

Arguably one of the most famous novels ever written, The Hound of the Baskervilles by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle is the perfect example of a standalone Holmes novel. In this, Holmes and Watson are hired by Dr James Mortimer to investigate the mysterious death of Sir Hugo Baskerville by an apparently demonic hound in the moors of Dartmoor. Mortimer believes that someone is systematically utilising the legend to eradicate the Baskerville line, and he believes Sir Henry Baskerville, the heir apparent, is next. As sordid histories regarding the Baskervilles get revealed, Holmes and Watson both realise that deep-seated resentment within the family tree is leading to this mechanical and possibly supernatural scheming to ensure the death of Henry Baskerville.

In the timeline of events, this story takes place before the events of The Final Problem, but Doyle wrote and published the story six years later due to the demand for more Holmes stories. The story almost exists in the limbo of Holmes’ existence, and this contributes to the standalone nature of the tale, reminding readers of Holmes’ powers of deduction, his banter, his relationship with Watson, and his quick wit. Besides, Watson has a substantial amount of real estate as a character without the shadow of Holmes cloaking him in its canopy; what also works is Doyle’s unique handling of suspense through pure gothic atmospherics, which palpably increases the element of horror in the tale, making the readers forget Holmes’ Occam’s Razor: “If you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” This perfectly encapsulates what “The Hound of Baskervilles” starts and unfurls itself as and what it ultimately proves itself to be.

This is the most adapted Sherlock Holmes story, featuring a whopping 26 of them across movies and television. However, one adaptation that almost screams perfection is from the 1950s, starring Peter Cushing as Sherlock Holmes and Christopher Lee as Sir Henry Baskerville. The haunting mystery of Baskerville Hall and the curse of the Baskerville lineage lend themselves to a gothic image, which Hammer Studios relishes to the fullest in this adaptation. Peter Cushing’s portrayal of Holmes is distinctive; he is sensitive, haughty, fidgety, and not the most friendly. Given how heavily the tale initially relies on Watson, Andre Morrell’s portrayal of the character is a remarkably strong version of the textbook Watson. In tandem, they create a world in tune with the supernatural, horror, folklore and consequential inter-generational violence.