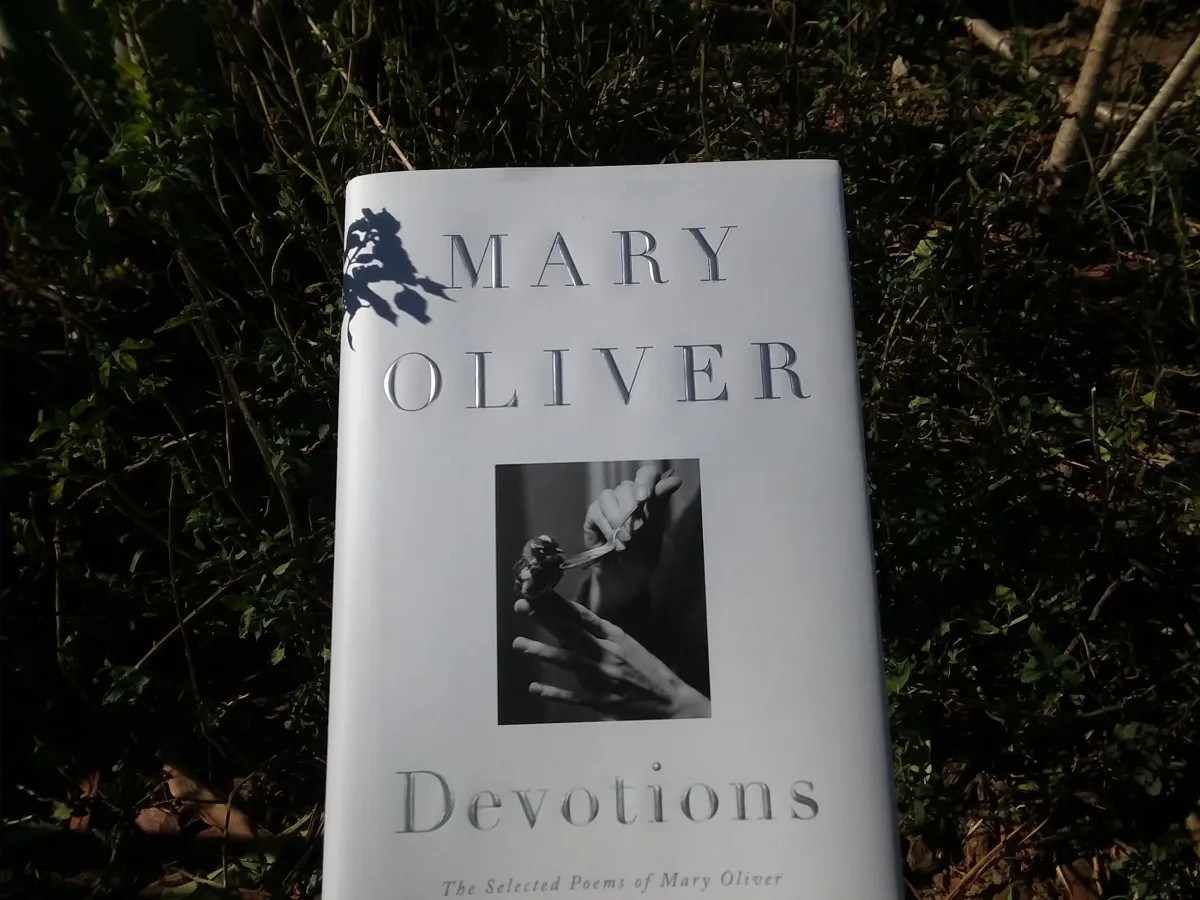

Read the review of one of Mary Oliver’s famous books of poems, Devotions, where poems speak in the language of nature.

‘Attention is the beginning of devotion’, observed Mary Oliver, a seeker who found life’s great questions mysteriously answered in the rhythms of the natural world and then reflected those quiet revelations within her poetic rhythms. Mary Oliver’s final collection of poetry, Devotions, is a fine selection of her life’s work as a devotee of nature.

Carefully curated by Oliver herself, Devotions showcases the poet at her edifying best – featuring works from her very first book of poetry, No Voyage and Other Poems, published in 1963 when she was twenty-eight, through her most recent collection, Felicity, published in 2015. Over the course of her long career, she received numerous awards, and her fourth book, American Primitive, won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1984. Spanning over five decades of her work and arranged in reverse chronological order, in Devotions, she provides us with over 200 poems, an extraordinary and invaluable collection of her passionate, perceptive, and much-treasured observations of the natural world.

Reflections in the Woods: Walking with Mary Oliver

Written in language that is as simple and accessible as a well-worn path through a beloved forest, Oliver’s words are bridges connecting with her habit of walking in the woods and quietly noticing whatever happens to present itself – now a hallmark of her poetry. Her verses read like threads of delicate incantations woven with wonder. Indeed, most poems in Devotions sound like prayers, with resonances almost biblical, yet a departure from the conventional – it is the creation that provides gazes into the Creator. In ‘Six Recognitions of the Lord‘, she says, ‘I know a lot of fancy words./I tear them from my heart and my tongue./Then I pray.’ She goes on in ‘Terns‘:

‘Listen,

maybe such devotion, in which one holds the world

in the clasp of attention, isn’t the perfect prayer,

but it must be close, for the sorrow, whose name is doubt,

is thus subdued, and not through the weaponry of reason,

but of pure submission.’

While rooted in the natural world, Devotions also carries a spiritual undercurrent, transcending religious boundaries and speaking instead to a universal sense of oneness and wonder – encouraging readers to find the sacred in the mundane, mindfully fostering a deeper connection to the mysteries of existence.

At the heart of Oliver’s poetic style lies her remarkable gift of observation, rendering the minutiae of the natural world in exquisite detail, transforming each poem into a sanctuary where readers can commune with the flora and fauna that populate her verses. What is certain is that the readers will find themselves traversing the terrain of her poetry with ease, where each step is a revelation, and each page turned, a whispered secret shared between kindred spirits.

Yet, within this observant exterior lies a wellspring of emotion, a depth of feeling that transcends the surface of descriptive language. Transforming the sensory into the emotional, and the tangible into the intangible, she captures, for instance, the dance of light on water not merely as a visual spectacle but as a metaphor for the fleeting moments of joy that grace our lives. ‘Sometimes I need/ only to stand/ wherever I am/ to be blessed’, reminds Oliver, who, in the hindsight of experience, knows ‘the way the old life haunts the new’ but is also mindful of the transience of our lives moments:

‘Nothing lasts.

There is a graveyard where everything I am talking about is,

now.

I stood there once, on the green grass, scattering flowers.‘

(From ‘Flare‘)

With simple words of wisdom carrying the weight of countless contemplative moments, each of her poems is a meditation, lending a deeper understanding of the self and the universe. The lesson is to integrate life’s experiences, in all its beauty and complexity, within the cycles of nature. Oliver reminds us, ‘They will be nourishment somehow (everything is nourishment somehow or another).’ It is from this perspective that she contemplates her place in the interconnected web of existence – while she watches a slippery green frog that went to his death in the heron’s pink throat – saying that ‘my heart dresses in black and dances’ with a realisation that the predator, the prey, and herself, are connected. She furthers this realisation in ‘Wild Geese‘ to tell the reader,

‘Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.’

The reminder is to find ourselves in the family of things and not in a hierarchy of power. For the world goes on without us, and pristinely so, as she remarks in ‘October‘:

‘One morning

the fox came down the hill, glittering and confident,

and didn’t see me – and I thought:

so this is the world.

I’m not in it.

It is beautiful.‘

By bringing the natural world to the fore, she constantly emphasises that humans are not at the centre of this world. That there are other beings whose experiences are equally important and, were we to keep aside our self-consciousness and pay attention, not very different from our own. In a gentle piece of advice, she says, ‘And what do I risk to tell you this, which is all I know?/ Love yourself. Then forget it. Then, love the world.’

Also Read: 5 Books That Will Help You Get Started With Reading on the Environment

Beyond the landscapes and creatures she describes, Oliver’s poetry is also an exploration of the human spirit – its resilience, its capacity for love, but most importantly, learning to embrace all our seasons just like the natural world. That ‘of course/ loss is the great lesson.’ But despite that, ‘I tell you this/ to break your heart,/ by which I mean only/ that it break open and never close again/ to the rest of the world.’

‘To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it go,

to let it go.‘

(From ‘In Blackwater Woods‘)

Exploring the complexities and tenderness of connection, and the inevitable pains of separation, Oliver reflects on the transformative power of love, both in its moments of joy and in its capacity to shape and redefine our understanding of ourselves and others.

Why Should You Read Mary Oliver’s Devotions

The strength of Devotions lies not only in the individual brilliance of each poem but also in the collective journey they offer. Devotions will serve as a companion for those seeking solace in moments of quiet contemplation. As Mary Oliver understood,

‘How people come, from delight or the

scars of damage,

to the comfort of a poem.‘