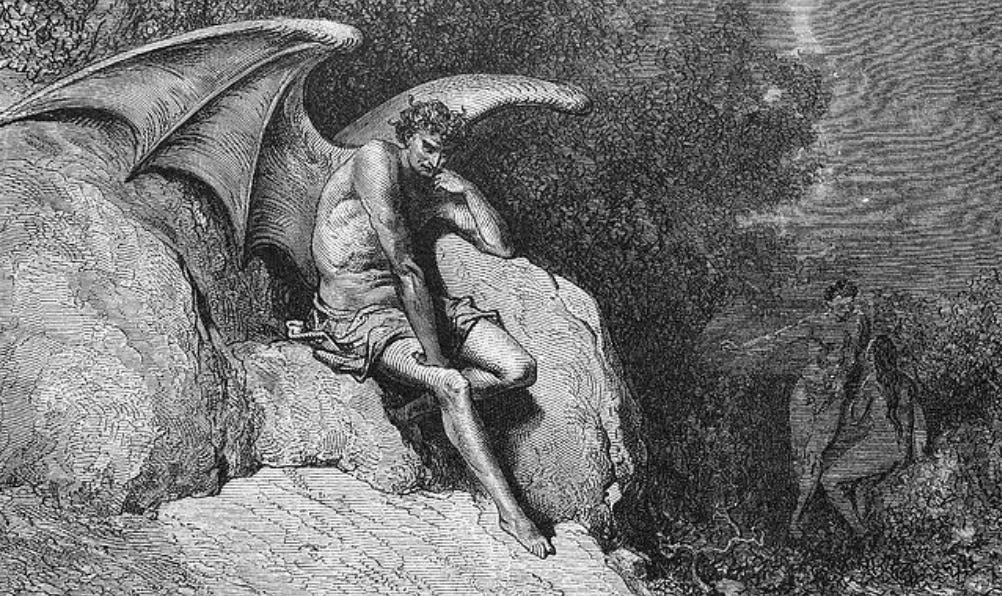

(The Fallen Angel by Julian de Medeiros)

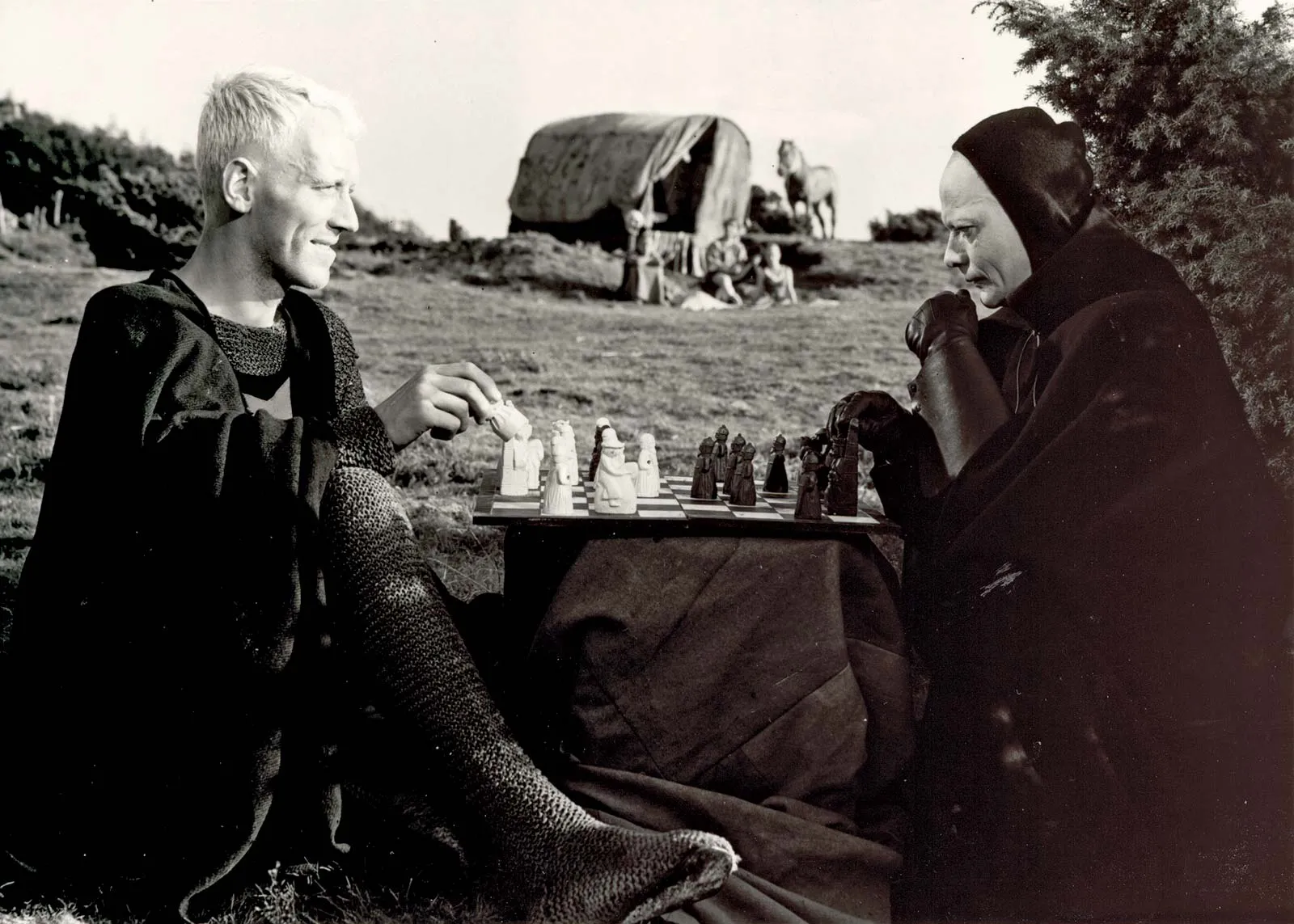

Humanity has long gravitated toward those who can articulate – or at least amplify – the fragile boundary between right and wrong. What matters is not merely offering answers to the collective, but shaping a mode of discourse, one capable of dragging us into an abyss or lifting us toward flight. Non-mythological fantasy emerged within artistic currents as a distinct enclave, often sidelined for straying too sharply from accepted norms. Yet its influence proved decisive. It nurtured crime, satire, mockumentary, and, above all, drama, precisely because it allowed narratives to be absurd yet reasoned, foolish yet grave within their own internal logic. Against this backdrop, when Ingmar Bergman conceived of “The Seventh Seal” as a reverent nod to Shakespeare, he understood that the story itself bordered on the illogical. Still, that apparent simplicity carried immense power, opening space to probe the farthest reaches of filmmaking and storytelling alike, on the page, on the screen, and in the uneasy silence between motion and meaning.

(The Seventh Seal, Ingmar Bergman; Courtesy: IMDb)

Khalid Jawed’s novel “Arsalan aur Behzaad” draws the enigmas of human consciousness into spaces that feel intimate, delicate, and unabashedly exposed. Within this terrain, we are neither ethical nor corrupt, neither virtuous nor fallen, but suspended beyond such binaries, removed from the scaffolding of a socially conditioned mind. Conversation becomes the lone medium through which thought unfolds, and introspection is no longer bound by memory’s reach or the limits of neural design. In the novel, good actions and malignant ideas are divided by a thin, shimmering line, yet that same tension settles like residue, clinging to what the characters leave behind as they part.

The Douglas Mackinnon-directed series “Good Omens,” adapted from the novel by Neil Gaiman, extends this inquiry further, tracing not only the evolution of its characters but also the human condition itself, especially at moments when it must summon the will to slip out of its own discarded skin. There is a raw calm in that act. Through it, we come to recognize ourselves more clearly, even as we learn to face what may be terrifying, yet still carries meaning. Within the show, we witness a decisive reframing of mainstream Christianity, one that suggests even what has lain absent for centuries can still shape meaning.

Such a belief gives rise to a message that resists rigid social frameworks because faith, in this rendering, invites expansion rather than confinement. Where one impulse urges us outward, toward possibility and reinterpretation, the other presses us inward, demanding restraint and compliance. It is precisely this tension, between transcendence and enclosure, that the show exposes, turning belief into a site of motion rather than a fixed idea.

(Good Omens. Courtesy: IMDb)

In the novel, Jawed makes it clear that fantasy does not arrive as spectacle or excess, but as a series of restrained, almost imperceptible nudges, moments where suggestion matters more than display. Nothing is pushed to an extreme. Instead, ambiguity does the job. The devil, in this sense, lives within both figures, just as fragments of wisdom and ethical reflection surface through them in different, often conflicting ways. Their sermons are not proclamations but leak ideas that spill quietly into the reader’s consciousness, urging a reconsideration of reality itself and the possibility of rescuing a larger truth for a meaningful end. Happiness, futility, madness, and transcendence all hover within reach, close enough to touch, yet never freely available. Both Arsalan and Behzaad must wrestle with their own internal limits, habits, and fears before they can even begin to feel these states fully.

This dynamic finds a striking parallel in “Good Omens,” where contradiction becomes the foundation of intimacy rather than its obstacle. Like Crowley, the demon, and Aziraphale, Arsalan, Tughral, and Behzaad discover a rare chemistry rooted in opposition as much as agreement. It is, after all, deeply human to build relationships not on purity or consistency, but on friction, shared doubt, and reluctant understanding. Closure, too, occupies a central place here. We often imagine it as something delivered by a single person who brings resolution into our lives. Yet in both “Arsalan aur Behzaad” and the series, closure is deliberately unsettled. Instead of sealing wounds, the characters disturb one another’s conditioned minds, stirring dormant fragments of the self. What emerges is not comfort, but awakening that is unsettling, necessary, and quietly transformative.

The Kenji Mizoguchi-directed drama “Sansho the Bailiff” engages with the same thematic core yet approaches it from a profoundly different direction, arriving at a conclusion where longing and suffering preserve something startlingly faithful to lived human reality. Rather than relying on abstraction, the film grounds its ideas in physical hardship and historical cruelty. As the central characters endure the violence and moral decay of feudal Japan, their repeated attempts to flee do more than promise freedom; they force an unavoidable reckoning with the stark brutality human beings are capable of inflicting on one another.

(Sansho the Bailiff. Courtesy: IMDb)

Even so, the narrative never surrenders entirely to despair. Within this oppressive world, love continues to surface in fleeting but persistent forms. Eyes still carry dreams, even when stripped of safety. Struggles remain hopeful, not because they guarantee victory, but because resistance itself becomes an assertion of humanity. What ultimately unfolds beneath the characters’ gestures and responses is the slow, inevitable collapse of long-held illusions. These delusions do not fade gently into acceptance. They fracture under pressure, reshaped by pain, endurance, and the refusal to abandon meaning altogether. In that fracture, Mizoguchi locates a quiet truth: human dignity survives not in escape, but in the difficult act of enduring while still choosing to feel.

In Jawed’s novel “Arsalan aur Behzaad,” the protagonists are shaped with equal complexity, though their journey unfolds inward rather than across historical violence. Their morbid desires and unfiltered thoughts would find little acceptance in the external world, and yet it is only within that very world that their destinies can finally take shape. To propel them forward, the narrative leans heavily into the psychology of Arsalan, a dreamer marked by a bipolar tension, where pessimism and optimism coexist without resolution. Their reflective minds become contested spaces, where moments of sharp clarity stand against blurred emotional terrain. Even as they attempt to anchor themselves in one another, they struggle against pride, constantly negotiating the meaning of staying, leaving, or, at times, annihilating each other, fully aware that their energies will remain inescapably bound either with each other or with the world they build around themselves.

When Martin Scorsese directed and released “Killers of the Flower Moon,” he was doing far more than translating David Grann’s account of the Osage murders to the screen. The film stands as a confrontation with a larger American spectre, what is often celebrated as the “American Dream,” yet functions as a quiet, enduring demon that has seeped into every household. Most families recognize it. Many accept it. And almost all are left carrying its weight for the rest of their lives. This was never simply a film about the murder of Native Americans, the original inhabitants of what is now called America. Instead, it becomes an act of refusal, rejecting the impulse to romanticize crime, an impulse that Scorsese himself helped define across decades of filmmaking.

(Killers of the Flower Moon, Courtesy: IMDb)

In doing so, Scorsese turns his gaze inward, using the film to dismantle his own cinematic language rather than refine it. Each scene feels like a deliberate striking down of familiar craft, as though he is testing which values still matter after a lifetime of mastery, even when age and legacy suggest there is nothing left to prove. The film insists that influence comes in two forms: through moral instruction or through the unfiltered exposure of reality. Here, Scorsese chooses the latter, peeling back the veil to reveal the inhuman forces that operate beneath the surface of an otherwise polished human narrative, forces that shape desire, ambition, and complicity far more than we are willing to admit.

Khalid Jawed pursues a similar confrontation in his novel “Arsalan aur Behzaad,” but his approach unfolds through restraint rather than spectacle. He sheds the heavy body of disgust and unbroken melancholy, not to deny their presence, but to make room for humour that is sharp, dry, and precisely placed, functioning almost like punctuation within the narrative. These moments of levity do not soften the text. Instead, they sharpen it, allowing the reader to breathe just enough to endure what follows. Through this tonal balance, Jawed takes aim at the deeper demon of Indian society, one sustained by puritanical morality and ritualistic comfort, where repetition passes for meaning and tradition substitutes for thought.

Jawed’s characters actively dismantle this inertia. They resist a social order that has grown so monotonous that the very acts we perform and the desires we pursue have gradually emptied themselves of purpose. The novel exposes society both through its characters and onto them, turning their minds and bodies into reflective surfaces. In doing so, it places a mirror directly before the reader, forcing a confrontation with what we are capable of at our extremes, both in our most depraved impulses and our rare moments of nobility. The text insists that erasure, whether of memory, discomfort, or contradiction, cannot guide a society toward any meaningful destination.

What remains, Jawed suggests, is language – raw, unapologetic, and indifferent to the need for moral cleanliness. This language does not concern itself with what it represents; it exists to articulate what cannot be comfortably held. Within this framework, even hatred is allowed its own coherence and weight. It carries meaning, structure, and intention, and cannot simply be replaced by love through moral insistence alone. Yet the novel does not surrender to despair. With care, attentiveness, and shared vulnerability, Arsalan can sit beside Behzaad, just as love can squat beside hate. They do not cancel each other out. Instead, they coexist, forming a more complete, if unsettling, portrait of human reality.

In the Spanish film “The Platform,” Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia uncovers how food can operate as both salvation and sentence, speaking louder than ideology ever could. Rather than turning appetite into a blunt weapon, the film stalks it, probing how different individuals respond when survival itself becomes conditional. Hunger here is not merely physical; it is diagnostic. Social structures are exposed as long-standing experiments that test people through food, defining taste, rationing desire, and then methodically draining resources until nothing remains.

The film sharpens this critique by mocking the very idea of appetite, slicing it along lines of region, caste, class, and religion, only to reveal a brutal truth. When nature turns merciless, these divisions collapse. In their place emerges a single, relentless instinct: people will stretch themselves morally, physically, psychologically towards whatever keeps hunger at bay. What unfolds is a horror rooted not in monsters, but in appetite itself. Under its pressure, we either forfeit our humanity or push past it, resigning ourselves to a form of existence that dulls reason and erodes our capacity to desire anything beyond immediate sustenance.

(The Platform; Courtesy: IMDb)

This confrontation is deliberate from the perspective of society, engineered and observed with cruel clarity. Yet once imposed on individuals, it works differently. Over time, resistance fades. The system no longer needs force. We are pulled into it unconsciously, adapting our values, instincts, and ethics until hunger becomes the sole language we understand. In “Arsalan aur Behzaad,” Jawed allows his characters to drain one another of hope and vitality, not out of cruelty alone, but to test whether they are capable of stepping beyond their own fixed ideas in search of resonance.

What binds them is a shared relationship that feels simultaneously parasitic and symbiotic, feeding and wounding in equal measure. We rarely recognize such bonds in our own lives because the colors we inhabit – routine, comfort, privilege – convince us that what we have is enough. Yet without a hunger for something non-material, something that resists definition or existence itself, we remain trapped in a different kind of starvation, one that keeps us obedient, compliant, and aligned with what authority quietly demands of us.

The politics of the novel move against the establishment, but never through a single, declared argument. Instead, it disperses itself across moments, silences, contradictions, and confrontations, enriching its purpose from multiple directions. The resistance here is not organized; it is felt. It grows out of exhaustion, longing, and an insistence on remaining present despite the odds. At its core, the novel carries a fragile prayer rather than a manifesto, one that refuses certainty yet demands endurance: I want to stay. I want to live. For a million years, without knowing whether it is possible or not.

Taken together, these works form a restless conversation about hunger of the body, of belief, of meaning, and about the fragile ethics that emerge when survival presses too close to the skin. From “Sansho the Bailiff” to “Killers of the Flower Moon,” from “The Platform” to “Arsalan aur Behzaad,” fantasy, history, horror, and intimacy are not escape routes but instruments of exposure. Each narrative strips away comfort to reveal how power feeds on desire, how systems test morality through deprivation, and how relationships, whether loving, violent, or contradictory, become the last sites of resistance.

What endures is not redemption in its grandest sense, but the stubborn insistence on staying, on speaking, on feeling even when meaning fractures. These texts do not promise resolution. They offer something more difficult and more honest: the courage to sit with contradiction, to recognize the demons we inherit and the ones we choose, and to acknowledge that humanity survives not by purity or erasure, but by the uneasy, necessary act of confronting itself.