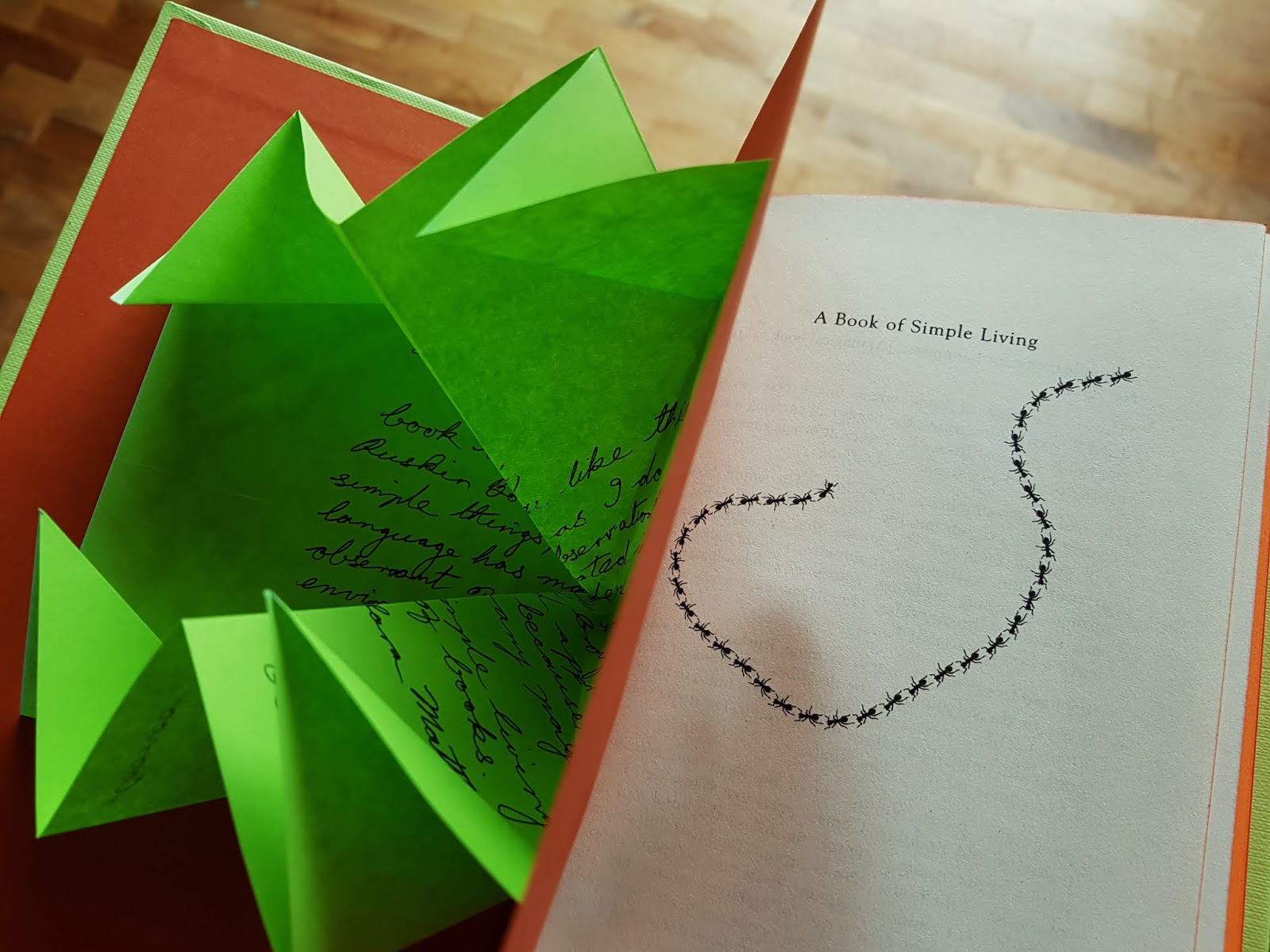

Come and travel with the author as we explore the simple philosophies of living the hilly-billy silly mountain life that Ruskin Bond professed in his A Book of Simple Living (2015)

If a man can be known by the ‘nature’ of his work, literally or more so, a child in us reminisces about Bond. This is not the Bond of the action paraphernalia, nor is he the creator of sensual thrillers. Ruskin is the village girl Binya, who replaces her invaluable leopard pendant with a bright blue umbrella. He is the bard of stories gathered in the Himalayan foothills, posing as the keen collector of observations on the night train to Deoli. The simple living that the matured Ruskin Bond transmits to his readers passes through an exhilarating osmosis. You got to read it to believe it!

This (re)collection of afterthoughts – A Book of Simple Living: Brief Notes From the Hill (2015 – is laden with prenatal innocence. He is seen to be embarking on a journey that passively pulls us up into an evergreen, euphoric individual. He begins his ‘Brief Notes from the Hills’ with an illustration showcasing the trail of ants. In Tao-esque virtuosity, the world of unanimous consciousness revolves around life. It exists as a tribute to the incredible puzzle of possible worlds, a manifestation of instant realizations, urgent contemplations and juxtaposed responses. The book starts with an epigraph by Leo Tolstoy – ‘In the name of God, stop a moment, cease your work, look around you.’

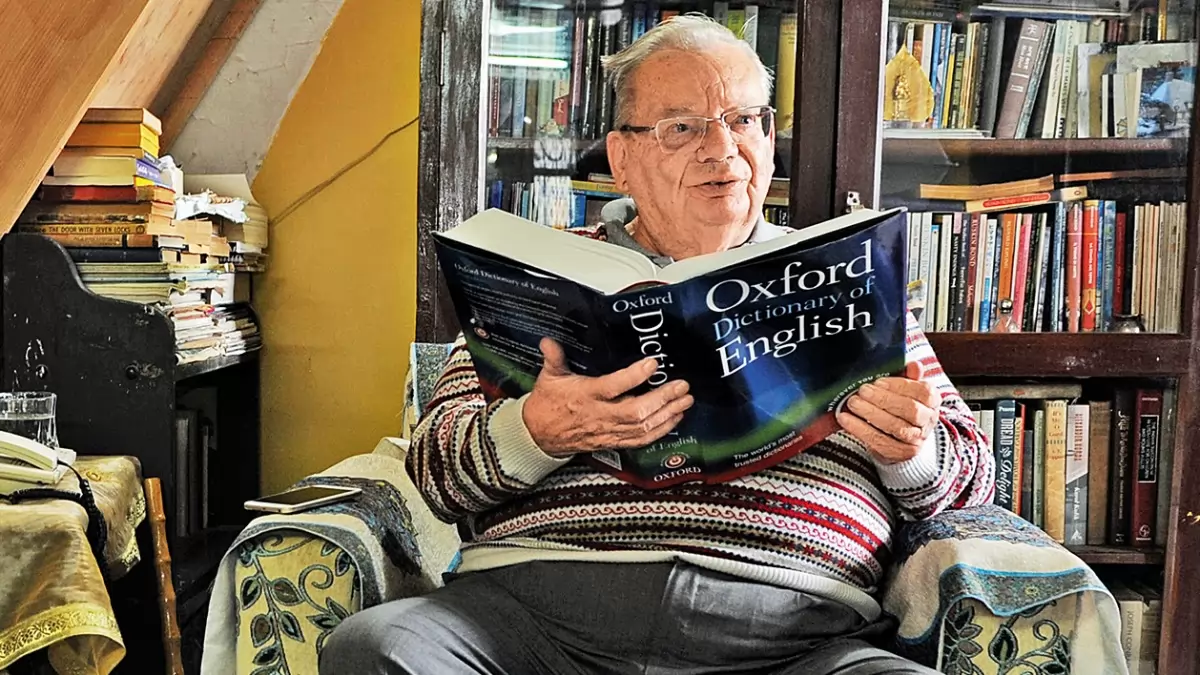

It is in a dynamic relationship with the self that the author exists in the milieu of the ‘All’. He asks, ‘What have I learnt after eighty years on planet Earth? Quite frankly, very little.’ Wisdom is taken in congruence with banality. It is only with an inherent opposition to the idea of a perfect world that one comes to accept the role of stillness, aka life. Ruskin Bond is an advocate of anti-management, a connoisseur of Time who tastes the moment with each passing juncture. When interviewed by News9 about the primary audience he writes for, Ruskin Bond replies, ‘I think, to begin with, one writes for oneself. Also, every writer has in his mind an ideal reader, which is a projection of oneself – maybe someone with a similar outlook, personality or way of life.’ Let us explore his revelations on a hilly-billy silly mountain life.

The Forest of Solitude and Birds

You wish for solace in his writings, and Ruskin Bond is synonymous with this solitude. The book is filled with instances of engagement, not with personified characters but with a singularly bountiful forest of species. He recalls a ginger cat visiting his terrace each afternoon, only to settle on the very same spot, with the same posture and pace. Attributing to his undulating sense of humor, Bond concludes the cat must be a monk. The night sounds of the monsoon posit as effervescent characters. The walnuts are polished, the pines whorled, the oaks gnarled, and the dark berries poked by the kokla and green pigeons of Garhwal. What makes Bond so appealing to the eyesight? The images that are opulently harbored throughout his oeuvre. He compares a couple of mynah birds, quarreling at the top of their lungs to initiate a human-like intolerance. The stage is set with black bushes, and ‘the grass keeps falling on the window sill’. The cuckoo shouts in unison: ‘I slept so well! I slept so well!’ A structure in temperament with the author’s illness, depicting the restlessness and sleepy nights he spent looking at his companions in amazement.

Life’s Humorous Ghosts

The book is sympathetic to ghosts of the dead past, yearning for their unobtrusive presence as well as their prolonged confidence. The song of the whistling thrush doubles as a score for his ‘screen of memory’. It is received in a bed of abundance, a fine wine that tastes better with age. Thus, the author proclaims – ‘Life hasn’t been a bed of roses. And yet, quite often, I’ve had roses out of season.’ Grief is a garland of happenstances, often garnered in the form of a feather. He compares humankind with the sarus crane or the seal who grieves the loss of a mate. It is the ‘touch of love’ that determines life, not the other way around. For him, it is gratitude and mystery, the satisfying mystery driving the innate experiences.

He considers his Delhi home as an incarcerating forum. Thriving alone and earning his lot since his early teens, Bond was never bound in a house arrest. Foraging through the medical examinations, he amusingly declares – ‘ECGs, ultrasounds, endoscopies, X-rays, blood tests, probes into any orifice they could find, and at the end of it all a fat bill designed to give me a heart attack.’ It is the small things that provide comfort, a plethora of listicles that do not end just with remembrance. In the manner of Georges Perec, Bond tries to emulate a user’s manual of life. However, time after time, he catalogs the sensory trebles. He shelters the gentle cooing of the pigeons in his nervous blood, the cricket playing hide-and-seek in a ‘shady nook’, or the frying onions in a household which voyeuristically deceives the menu for the day. Ruskin Bond is an endless bundle of thoughts as he does not induce a radical stricture to his observations. A kiss in the dark and the ‘deep purple sky’ are equally his treasure troves, if not his placard.

Also Read: A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara Review: Time Will Tell, in its Passage Handled Well

Reading, Travelling, Aging

His words are greatly inspired by the likes of Robert Louis Stevenson and Burroughs, often enigmatically associating the weary resting beds of the traveler with the maxims of renunciation. Bond dons the hat of Zen, inculcating a prayer for children who are beginning to appreciate the ‘gentlest of Gods’ – sleep, as Ovid says. He instills a deep sense of enchantment in his dreams – ‘Forget and forgive at sunset, and then the day’s deeds are truly done. Then sleep.’ Could it be simpler than this? Or, should I ask, as Kundera does, will ‘simple’ become a heavy word in the intense lightness of living? One wonders.

Ruskin Bond honors the pace of aging. Life overgrows like a banyan tree, but it’s not us who grow old. The younger self does, free-falling into the abyss of time. He rightly asserts that his books are old, and so are his pictures, shoes, typewriter and only suit. But, he unhesitatingly instigates, ‘Only I am young.’ The objects in his purview are rehearsals for the cinema of life. The constant hooting of the owl is a challenge for the microscopic eye, yet it resonates around the ‘raat ki rani’ as if a speaker’s getting tested amidst the horrid silence of the jungle. Meanwhile, while the window is shut, ‘a star falls in the heavens’. Ironically, it is a beautiful dead thing and a speck that makes us.

An Onrush of Natural Prose

If you ask why it’s necessary to devour the prose of Nature, Ruskin Bond has an answer. He talks about a recent encounter when he was asked, ‘Is Nature your Religion?’ The author answers in the negative. Even though living close to Nature prevents one from getting easily broken, it’s also equally true that it does not promise anything. It is its hearty uncertainty that replaces the dependency on rewards, protection from foe and promise of wealth and progeny. Instead, Bond defines his work as an overwhelming Renewal, the beauty of the seed and the despondency of the day. Nature is contingent, but it is transcribed in movement. As all machines rust and great wars crumble civilizations to dust, the earth is blanketed in a fire-bed of grass and wild dandelions. Without a speck of confusion, Bond knows ‘Nature is the reward in itself.’

Why Should We Read Ruskin Bond?

While residents were demanding the secession of Uttarakhand in 1994, Mussoorie had been put under curfew for a number of days. The picturesque Mall turned into a death camp within a few hours, splashing blood on the clouds of peace. The tragedy of the rich autumnal flora was never confined to a household. The impact was felt amidst the bright red branches, and grief never left their side. Ruskin Bond teaches us to be recalcitrant in this sorrow. He recompenses tragedy with an immense will to live.

When living in Jersey, a law-abiding island in the UK’s Channel, Bond witnessed all residents peacefully going about their business under German occupation during World War II, without paying any heed to the same as long as their fishing and farming were unaffected. When the war ended, their tomatoes kept growing as ever before, and they simply went on with a gutsy air of freshness. Hence, simple living is where he assures us all – ‘When all the wars are done, a butterfly will still be beautiful.’