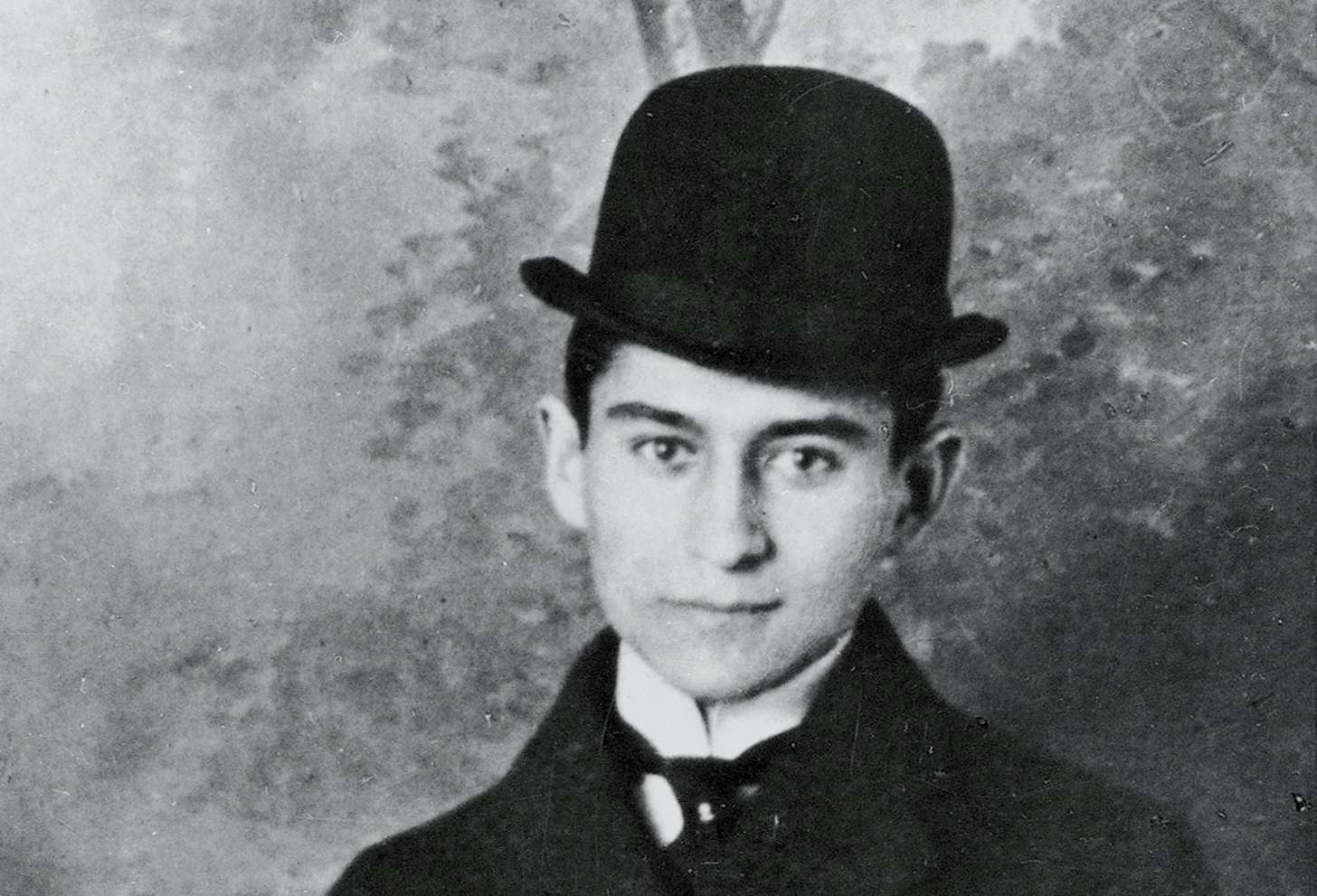

Who is Franz Kafka?

Franz Kafka was born in 1883 in Prague, part of the then-Austro-Hungarian Empire and the current capital of the Czech Republic. He lived a short life, studying law and working a desk job, spending most of his free time writing the iconoclastic, surreal, and absurd narratives which he would become known for. A large majority of these works would only be published after his death. He died in 1924 at the age of forty. Upon his death, he instructed his friend Max Brod to destroy most of his writings. Thankfully, Brod went against his friend’s wishes and instead had them published; by the end of the second World War, Kafka’s name would be recognized around the world. He is now popular as the emblematic voice in twentieth-century literature. The term ‘Kafkaesque’ has been embedded in popular culture and is used to describe similar, odd experiences to those written about in his stories and novels. Many of his works have been adapted to theatre and film; notably, filmmaker Orson Welles adapted his best-known novel, The Trial, to film in 1962.

What does Kafka’s writing have to do with the body?

Kafka’s wonderfully imaginable — yet dark and often gruesome — stories thrust the reader into an uncanny world in which characters encounter strange monsters and even stranger people and in which things move and happen as if in a dream. In these stories, we find many odd characters. For example, a monkey who learns to talk and then becomes an alcoholic and a man who finds himself, one day, irreversibly transformed into a large beetle. Kafka takes what is most common, ordinary, and every day. Then, he flips it on its head, spins it in circles, and sends it outside for a walk through city streets.

The worlds Kafka creates are uncanny and off-putting. And yet, they immerse the reader, drawing them in and helping them find meaning in these worlds. How does he take these fantasy worlds and make them feel REAL? He does this through a detailed commentary of his character’s physical experience, sensations, and surroundings. Kafka’s description of physical experience allows the reader entry into that character’s world. The ways in which Kafka describes these experiences are incredibly vivid. While reading these stories, we often find that we can almost feel what the character is going through. These moments tend to send a chill down one’s spine.

In “A Country Doctor,” for example, a completely naked narrator is dragged by horses through a snowstorm: “slowly, like old men, we crawled through the snowy wastes… Naked, exposed to the frost of this most unhappy of ages.”

The narrator of “The Metamorphosis,” Gregor Samsa, wakes up one day and finds himself transformed into a beetle. Now, this is surely nothing anyone has really experienced for themselves. Yet, through the description of Gregor’s physical sensations, Kafka forces the reader to understand his helplessness and suffering. He describes Gregor lying in bed, waving his thin, beetle legs uselessly in the air, staring at the ceiling. He describes Gregor struggling out of bed and going over to the window, straining to pull himself up to see out of it — something which would have been so easy in a human body. Through these descriptions, we know not only what Gregor is thinking but what he is feeling too. Kafka immerses the reader in Gregor’s existence, in his mind and his body.

In these ways, Kafka’s worlds become more than just imaginary universes. They become vivid dreamscapes, which are nonetheless truly real for being spectacular and absurd. We plunge into and experience these dreamscapes along with his characters and through the bodies of those characters and their sensations — the sensations of their skin and eyes, their breathing, and their walking. We can immerse ourselves in the narrative. These are worlds that we can feel around them and absorb in such a visceral manner because Kafka, skilled as he is, understands how our bodies perceive the world around us.

What can we learn about the human body and its suffering from these stories?

Kafka uses the pain and pleasures of the body as a window into the human soul. Through descriptions of physical experience, he opens a vault of powerful and uncanny — almost supernatural — emotions, emotions which are most difficult to put into words but which Kafka somehow grasps and makes us, the readers, feel for ourselves.

Perhaps most emblematic of these emotions, and, in particular, how they are found in physical sensation, is the story “In The Penal Colony.” It is a story of guilt, horror, justice, and retribution. The narrator of the story is a worn traveler. Set in an unnamed penal colony, where the traveler is visiting, he is brought to witness a certain peculiar method of execution. The condemned man is laid flat on the surface of a strange machine. The executioner goes on to describe in detail to the traveler how the machine works, and then he demonstrates its function on the body of the condemned man. The traveler watches as the machine carves, very slowly, the sentence of the condemned man into his body until, after a length of twelve hours, the man dies. Furthermore, the condemned man does not know prior to these proceedings what his sentence is. He only comes to learn what he has been charged with deciphering the letters engraved in his flesh by the blades of the machine. During the second half of the twelve hours that the machine takes to inscribe the legal sentence in the condemned’s flesh, it is typical, so the executioner explains, for the condemned to experience a religious epiphany.

The whole process of execution is described in infallible detail by Kafka. The horror of the condemned man, his pain so intense as to force vomit from his mouth, and the inscriptions written by the machine’s blades on his body are made palpable through Kafka’s writing. The condemned’s guilt and the justice, which punishes it, are chiseled into his flesh. Justice makes the man pay for his crimes through physical suffering; through this physical suffering, the man even achieves religious inspiration and perhaps the retribution of his soul. The condemned is forced to suffer, and if he accepts his suffering with courage, he finds salvation. This salvation is found through the overcoming of physical pain.

Here, Kafka uses physical pain as a measure of a man’s guilt and his reaction to that pain — his strength in the face of it — as a measure of his potential for salvation. “In The Penal Colony” studies a popular trope of literature: the overcoming of pain and the attainment of spiritual retribution; but, in a typically Kafkaesque manner, the story is mutated so that the overcoming of pain is not the overcoming of external obstacles, but instead the overcoming of the internal suffering of one’s own body: the story is a study of strength in the face of physical pain, which is the most immediate form of suffering. Kafka’s condemned man confronts heads on both his guilt and the possibility of his retribution in the form of immediate and intense physical suffering. Here, the body is no longer only a vessel for the soul; but rather the seat and the manifestation of the soul. Therefore, this means that the spiritual epiphany experienced by the condemned is only made possible through confronting this horrific physical experience.

His experience of pain is made clear to the reader because they can easily sympathize with the pain of the condemned. They might even imagine the machine operating on their own body, and the reader will surely not have trouble imagining the immense — and truly spiritual — emotions which would consume them if they had been punished in this way. And if they had felt that intense pain for so many hours.

Obviously, this method of torture is incredibly unrealistic and pragmatically untenable. But Kafka describes it as if it were real, and he brings the machine into the level of reality by describing in detail the experience of it operating on one’s body. He forces the reader to gape in horror as the torturous process unfolds in front of them. Given how sure “In The Penal Colony” is to make on a reel with disgust and upset in the stomach, we might even say the story is a method of torture in itself.

Conclusion: What does Franz Kafka see in the body’s suffering?

Franz Kafka opens up the human body, looks into it, and describes its most inexorable pains. What is Kafka seeing when he looks into the human body? What does he wish the reader to see when he describes the body and its sensations? Perhaps, in physical pain, Kafka saw the root of all human suffering, sin, and guilt. Perhaps in physical pain, he saw what was universal to all humankind, or he saw that what is most common to all people is their will to fight against that pain, to transcend the suffering which binds us all. In describing the suffering of the body, he shared his pain with us, and in reading his stories, we share our pain with him. Perhaps this is true. Literature is the collective will to overcome suffering and transcend the pain we hold within our flesh, tired muscles, and tensed joints. As Nietzsche once said, the body is the war and the peace of existence.

Franz Kafka certainly did confront the pain of his own body through his writing. The author died while editing his story, “The Hunger Artist.” The story is about a performer who would not eat for weeks on end. He continued fasting for so long that people forgot he was even there. Eventually, he dies on a bed of straw in the cage he had performed in. The narrative seems to mirror Kafka’s own life in his final days: Kafka’s throat had been swollen shut by tuberculosis, it was too painful for him to eat, and eventually, the writer, too, died of starvation.

Also, Read

Poetry Of Hannibal Lecter’s Character Design

Pride And Prejudice: What Makes It Still Relevant?

1 thought on “The Endurance of Physical Suffering in Franz Kafka’s Stories”

Comments are closed.