Celebrations of the Turkey Holiday, or what we call Thanksgiving, spread across the globe on 23rd November this year. It is not a surprise that it is celebrated across the planet at various intercontinental zones. Be it the United States, Grenada, Liberia or Norfolk Island in the Australian Territory, Thanksgiving marks a significant end to the passing year. Harvest festival holidays, similar to those in Japan or India, commemorate the vital elements of our existence, that of our crops and the stimulation that the preceding year has provided to us. The fourth Thursday of November is laden with cultural and religious connotations, and how far can literature fall behind? Here is a list of 5 essential books for Thanksgiving that instigate the purity of gratitude and bless us to perceive through our open eyes the extensive dynamism of a world that is bountiful with love, laughter and life.

Boy: Tales of Childhood (1984) by Roald Dahl

The book marks an autobiographical sketch of Dahl’s early days, marking a transition from his childhood ancestry to his entry into the public school system. Exploring the conditions that he had to face while acclimating to the notorious public school system of the 1920s and 1930s, Dahl comes alive in his own story in the unique and amusing style that he is known for. He draws upon the days of his father, Herald Dahl’s accident when the latter broke his arm while repairing the ceiling ties at home. A drunk doctor mistook his arm for a dislocated shoulder and attempted to pull it to the right place, only to compel an amputation. The book is laden with such triumphs that do not deter the spirit of men, for as soon as he was able to return to his chores, Herald learnt to use a sharpened fork for his meals, failing once in a while to cut off the top shell of an egg. Similarly, his mother, Sofie Magdalene Hesselberg, was a woman 20 years younger than his father, who single-handedly took the helm of the family livelihood and decisions on the education of children. With the arrival of her fifth child, she shifted to a smaller Cumberland Lodge.

He narrates an event when his friend’s father had warned him against buying the Liquorice Bootlaces, threatening them with a disease called Ratitis. In the chapter ‘The Great Mouse Plot’, the author took on this false scare and put a dead mouse inside one of the Gobstopper jars in one of the sweet shops. The subsequent poster reads ‘WANTED FOR MURDER’ and a ‘swish-crack’ from the cane marks the end of this adventure. Roald Dahl expostulates on the vivid experiences of his lifetime and manages to survive despite the harshest conditions. We took upon the ravishing details with a pinch of salt and sat down with the book to gobble up the ‘craggy mountain of home-made ice-cream’ and ‘thousands of little chips of crisp burnt coffee (that Norwegians call krokan)’, as expected on a chilly, winter night.

Mrs Frisby and the Rats of NIMH (1971) by Robert C. O’Brien

Illustrated by the celebrated Zina Bernstein, this book takes us on a massive joyride as we read the tale of a widowed mouse, Mrs Frisby, in a mission to save his son Timothy with the help of the rats. This fantasy book for children is a lesson embodied in its characters, a family of mice that struggles to survive on Mr. Fitzgibbon’s farm, dreading the spring due to its tractors and the destruction of her precious home. As Timothy is too sick with pneumonia to accompany them on the ‘Moving Day’, Mrs. Frisby reaches out to a dear family friend, Dr. Ages and a crow named Jeremy, who fly her down to her humble abode, saving her from the attacks of a dangerous orange cat named Dragon. The wise owl suggests she seek help from the rats living in the rosebush of the farm, and they quickly follow through as her husband was a martyr on the battlefield, trying to poison the cat.

It is a tale of comradeship and mutual understanding, gratuitous in its outreach and humanization. It shows its young readers how rats were hatefully isolated, designated to be disease-spreading rodents. On the contrary, the rats’ intelligence helped them escape the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) where they learnt to read, write and escape the experiments that they were subjected to. The motto of the story resonates throughout the tale: “All doors are hard to unlock until you have the key.” The rats were well-versed in the tales of the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans as well as the Dark Ages ‘when the old civilizations fell apart and the only people who could read and write were the monks.’ Thus, the book stands as a testament to respect, honor and assistance, the constitution of the modern world.

The Giving Tree (1964) by Shel Silverstein

Originally published in 1964 by Harper & Row, this American children’s picture book teaches us more moral foretellings than one. Translated into a number of different languages, this book talks about a tree and a young lad, whose transitions keep him from sharing the same relationship with the tree as he had done in the previous decade. Trees grow with time, but they seldom age. The boy with his human characteristics tends to fall apart from his beloved tree. When he was too little to judge, the boy ‘would gather her leaves’ to turn them into ‘crowns and play king of the forest.’ Climbing up its branches, he would swing branches and collect apples. However, with the passage of time, the boy seemed to drift from his daily habits, focusing on his boredom, romance and familial duties. Thus, the tree was lonely.

“I want to buy things and have fun. Can you give me some money?”

“I have only leaves and apples. Take my apples, boy, and sell them in the city. Then you will have money and you will be happy.”

The ever-growing demands of the young lad kept on being satisfied by the tree until he cut off its branches to provide his wife and children with a house to live in. With the adverse penury and old age, the boy demanded a boat to sail away and the tree offered its trunk. In a melancholic ending, the tree declared: “I am sorry boy, but I have nothing left to give you.” The magnificent tree was left with a bereft stump, but its goal was to console the boy. This sacrifice is unprecedented as it confesses: “well, an old stump is good for sitting and resting. Come boy, sit down. Sit down and rest.”

Green Eggs and Ham (1960) by Dr. Seuss

This book by Dr. Seuss has been sold 8 million times around the world, and we don’t doubt it! This story has also found a place in a Netflix series, animated with the same title. The character Sam-I-Am takes on the task of making a man try the dish, green eggs and ham. The repetitive denial on the part of the man is not paid heed to, as Sam-I-Am continues to indulge in the pleasure of persuasion and dutiful convincing skills. The story revolves around this apparent contradiction between these two characters, resulting in a constant conflict between the two. The man proclaims that he seriously hates the food, while the adamant Sam keeps pestering him to modify the environmental surroundings so that his meal would be enjoyable. He suggests locations like the box, house, tree, car, train, rain, boat and even in the dark! He goes on to the extent that he offers condiments and accompaniments like sides of mice, foxes and goats. This method of inducement and coercion may seem controversial to some, but it is important to comprehend the value of all food items and appreciate the diversity that it has to offer. The man finally agrees to try it (hoping to get rid of Sam), but, as a conclusion, he ends up feeling happy after the delicacy is tasted. This is a phenomenal addition for today’s youngsters who often fall victim to the intricacies of ‘cancel culture’ and fall into the conviction of peremptory negatives.

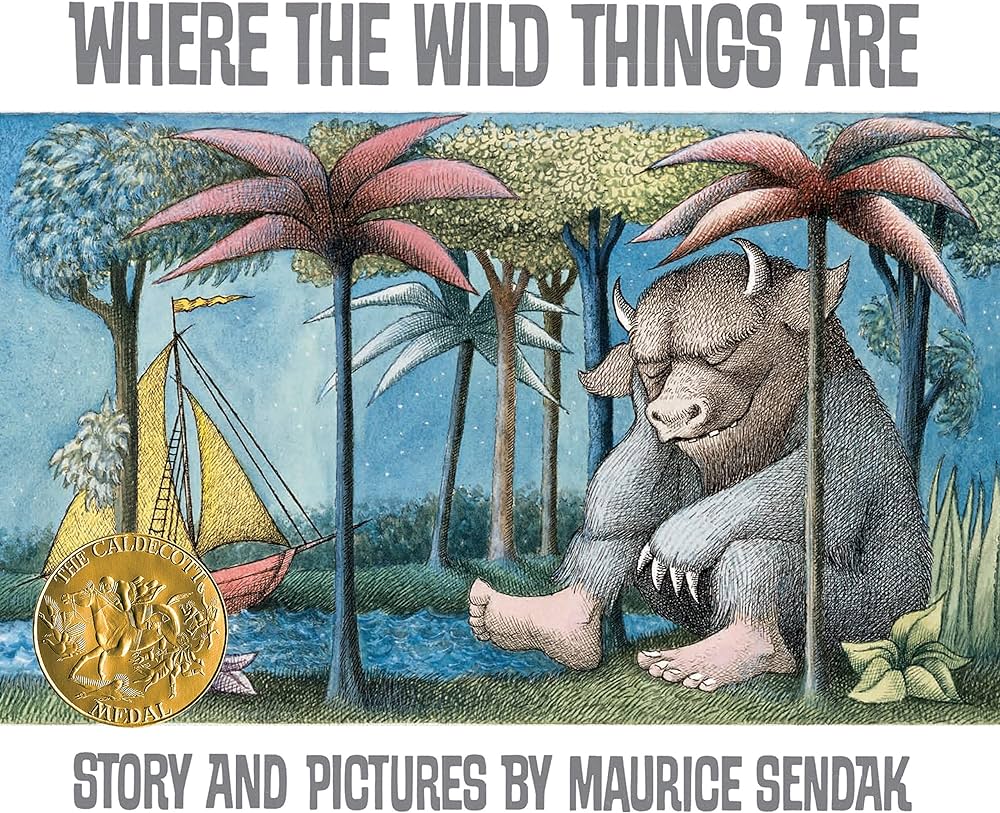

Where The Wild Things Are (1963) by Maurice Sendak

Also published by Harper & Row initially, this children’s picture book has also gained immense popularity worldwide, being a testament to recognizing the imminent purpose of flora and fauna all around us. The book has received numerous accolades, voted as the number one picture book in a survey conducted by the School Library Journal in 2012. The story revolves around a young boy, Max, who dresses himself up in a wolf suit and starts teasing the animals all around the house. His mother scolded him, yelling ‘WILD THING!’ but Max dared to reply ‘I’LL EAT YOU UP!’ only to be grounded in his room. His setting gradually transformed into a supernatural world, filled with a forest of mysterious trees. Max sailed off into the ocean and when he reached the shore, the wild things ‘roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws.’ Scaring the creatures with his elaborate gestures and staring at them without blinking did the trick. He was pursued as the King of the Jungle, elaborated with his grotesque beauty. The author replaced the horses in his book with caricatures of his uncles and aunts, enabling his readers to pay attention to the energy of the youth. The chaos created by adulthood, for him, was far more damaging than the restrictions imposed on kids. Max, thus, slowly but surely, gets bored of being the solely respected creature in his world and wishes to get back to the restraint of home. This book teaches our youngsters the law of contrasts and initiates a knack for careful thoughts before leaping into possible actions.